Introduction

Memory is often imagined as a video recorder that faithfully captures our experiences. Yet decades of research in cognitive psychology have demonstrated that human memory is fundamentally reconstructive, error-prone, and deeply influenced by emotions, expectations, and social contexts. False memories—recollections of events that did not occur or occurred differently than remembered—represent one of the most striking examples of our mind’s imperfect nature. These inaccuracies are not signs of cognitive failure but rather byproducts of the brain’s adaptive strategies for efficiency and meaning-making.

Read More: Ragebait

Memory as Reconstruction, Not Replay

Foundational research shows that memory is not a reproductive process but a reconstructive one (Bartlett, 1932). Rather than storing exact replicas of events, the brain encodes fragments of information and later reconstructs them using knowledge, schemas, and contextual cues. This reconstructive nature means that memories can shift over time, particularly when influenced by new information or reinterpretations.

Cognitive psychologist Elizabeth Loftus, one of the leading researchers on false memories, demonstrated that even subtle suggestions can distort people’s recollections (Loftus, 1975). Her work highlights that memory is highly malleable and susceptible to external influences.

How False Memories Form

Some ways that false memories form include:

1. Encoding Errors

Memory distortions often begin at the moment of encoding. When attention is divided or when an event is highly complex, the brain may encode incomplete or inaccurate representations (Schacter, 1999). These gaps increase the likelihood that reconstruction will draw on assumptions rather than actual experience.

For example, a witness to a fast-paced or traumatic incident might encode only broad details, leaving the specifics vulnerable to later distortion. This is not a flaw but an adaptive strategy that prioritizes survival-relevant details over exhaustive recording.

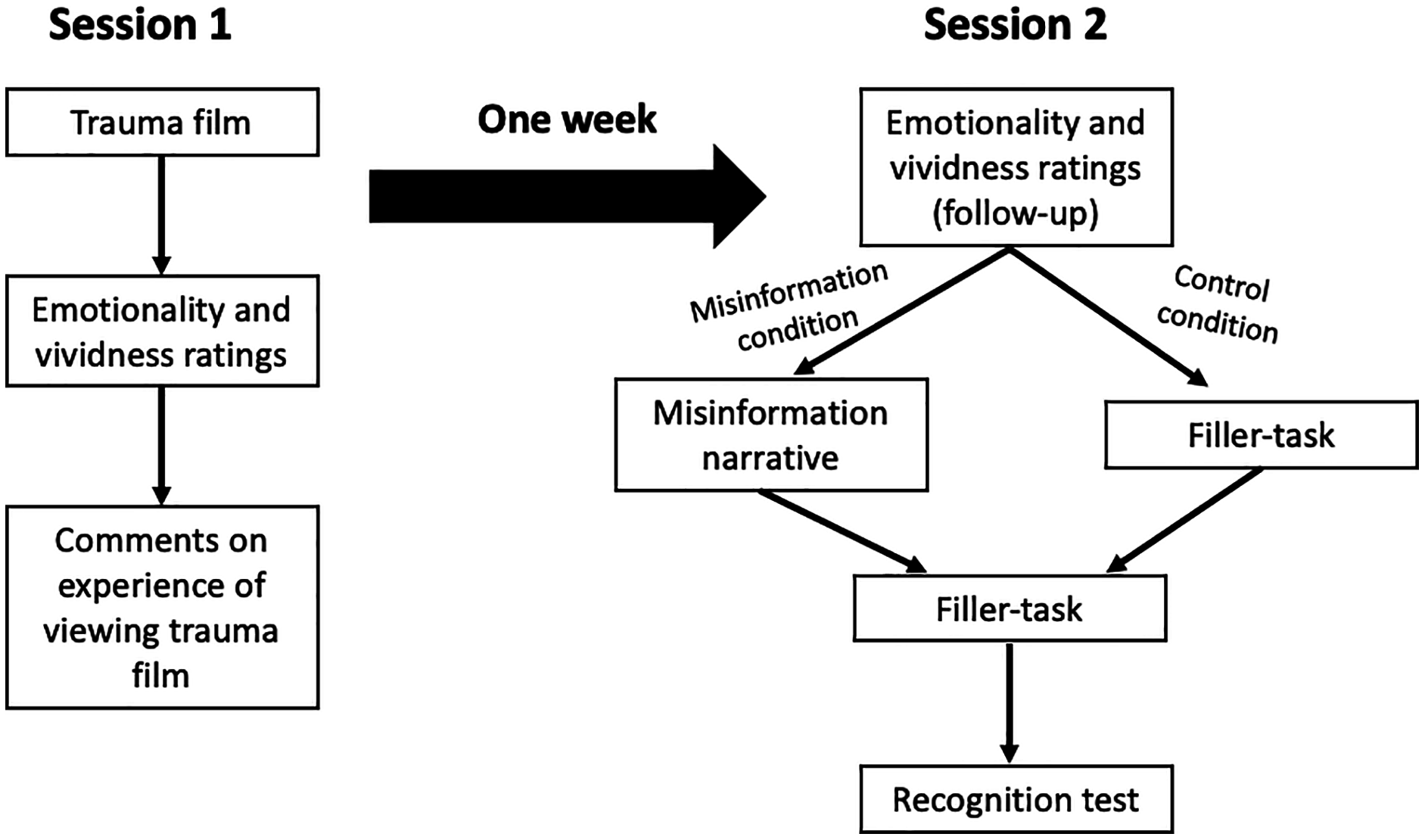

2. Suggestibility and Misinformation

The misinformation effect—an extensively documented phenomenon—occurs when exposure to misleading information after an event alters memory recall (Loftus & Palmer, 1974). Even subtle changes in wording can alter recollections. For example, asking how fast a car was going when it “smashed” into another car leads to higher speed estimates than using the word “hit.”

The brain integrates the misleading detail into the original memory, and individuals may even feel highly confident in their inaccurate recollections.

3. Imagination Inflation

Imagining events increases confidence that those events actually occurred, a phenomenon known as imagination inflation (Garry & Polaschek, 2000). When people vividly imagine an event—such as being lost in a mall as a child—they activate similar neural networks involved in actual memory retrieval (Schacter & Addis, 2007). Over time, the imagined scenario may be mistakenly interpreted as a memory.

4. Source Monitoring Errors

A major contributor to false memories is the inability to correctly identify the source of a piece of information (Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993). People may recall a detail but mistakenly attribute it to the wrong time, place, or person. For example, a person might remember a conversation from a movie and misattribute it to a personal experience.

Source monitoring errors are particularly common when memories are emotionally charged or when individuals are under stress.

5. Social and Cultural Influences

Memory is shaped not only by cognition but also by social dynamics. Conversations can introduce new interpretations, and repeated storytelling can exaggerate or alter events (Hirst & Echterhoff, 2012). Social pressures, such as the desire to align memories with group narratives, further contribute to distortion.

Cultural schemas—shared patterns of interpretation—also shape memory. People may misremember details in ways consistent with cultural expectations rather than objective reality (Wang, 2006).

6. Emotional Interference and Trauma

Emotion plays a complicated role in memory. While emotional events are often remembered vividly, the details are not always accurate. Research shows that strong emotions enhance memory for central features but degrade memory for peripheral details (Christianson, 1992).

In some cases, traumatic memories may be incomplete, fragmented, or reconstructed from limited information. This does not imply fabrication but highlights that the brain prioritizes emotional intensity over accuracy.

Neuroscience of False Memories

Neuroscientific studies show that true and false memories activate overlapping brain regions, including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Schacter & Slotnick, 2004). False memories often involve similar neural patterns as true memories, which explains why they can feel just as vivid and convincing.

Functional imaging studies reveal differences only in the fine-grained activation patterns: true memories tend to activate more sensory-specific areas, whereas false ones rely more heavily on semantic processing (Dennis et al., 2012). This distinction underscores that memory relies not only on sensory data but also on meaning-based inference.

Why Memory Is Designed to Be Fallible

From an evolutionary perspective, memory’s fallibility is not a design flaw but an efficient adaptation. Storing exact replicas of every experience would be energetically expensive and cognitively impractical. Instead, the brain stores essential information—patterns, meanings, and emotionally relevant cues—while discarding or compressing details.

This strategy allows for flexible thinking, future planning, and generalization. In fact, the same neural processes that support imagination and creativity also contribute to memory distortion (Schacter et al., 2011). The brain’s capacity to simulate future events relies on its ability to recombine fragments of past experiences.

False Memories in Legal and Clinical Contexts

The malleability of memory has significant implications for the legal system. Eyewitness testimony has long been considered compelling evidence, yet research shows it is vulnerable to distortion (Wells & Olson, 2003). Misidentifications contribute to wrongful convictions, emphasizing the need for careful interview procedures and corroborating evidence.

In clinical contexts, therapists must be cautious when exploring past trauma. Suggestive questioning can unintentionally lead to the formation of false memories, particularly in vulnerable individuals (Lynn et al., 2015). Responsible therapeutic practice emphasizes grounding techniques, open-ended questions, and patient-led narratives.

Reducing False Memory Susceptibility

While false memories cannot be eliminated, certain strategies reduce vulnerability:

- Encouraging critical thinking: Awareness of biases and misinformation helps individuals scrutinize new information more carefully.

- Using non-leading questions: This is crucial in investigative and clinical settings.

- Promoting mindful attention: Reducing distractions improves encoding accuracy.

- Recording or documenting events: External records reduce reliance on fallible recall.

- Emphasizing metacognition: Understanding that memory is not always accurate promotes healthy skepticism about emotionally charged recollections.

Conclusion

False memories demonstrate that memory is not a passive storage system but a dynamic, reconstructive process shaped by cognition, emotion, and social context. Although memory’s fallibility can lead to misunderstandings or inaccuracies, it is also essential for adaptive functioning, creativity, and meaning-making. Understanding why we misremember things allows us to navigate the world more intelligently, communicate more precisely, and make better decisions in legal, clinical, and interpersonal settings. The science of false memories ultimately reveals as much about how we interpret reality as it does about how we recall the past.

References

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology.

Christianson, S. A. (1992). Emotional stress and eyewitness memory: A critical review.

Dennis, N. A., et al. (2012). Neuroimaging of true and false memories: A meta-analytic review.

Garry, M., & Polaschek, D. L. (2000). Imagination and memory.

Hirst, W., & Echterhoff, G. (2012). Shared memories in social groups.

Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring.

Loftus, E. F. (1975). Leading questions and the eyewitness report.

Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. (1974). Reconstruction of automobile destruction.

Lynn, S. J., et al. (2015). Memory and suggestibility in clinical practice.

Schacter, D. L. (1999). The seven sins of memory.

Schacter, D. L., & Addis, D. R. (2007). Constructive episodic simulation.

Schacter, D. L., et al. (2011). The future of memory.

Schacter, D. L., & Slotnick, S. D. (2004). Neural bases of false memories.

Wang, Q. (2006). Culture and the development of memory.

Wells, G. L., & Olson, E. A. (2003). Eyewitness testimony research.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,043 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, December 7). False Memories and 6 Important Reasons How They Form. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/false-memories/