Introduction

Overthinking is something nearly everyone experiences at some point: spiraling thoughts, obsessive replaying of conversations, or predicting worst-case scenarios long before they unfold. While thinking is a uniquely human strength — enabling planning, creativity, reflection, and innovation — it can turn against us when the analytical mind becomes a looping trap. Overthinking is not the same as problem-solving; instead, it is repetitive, unproductive mental activity that increases stress rather than resolving it. Many people describe it as being mentally “stuck” even though they desperately want to move forward.

Psychologists commonly distinguish between two primary forms of overthinking: rumination, which focuses on past events and perceived failures, and worry, which focuses on future uncertainty and threat (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Both forms drain emotional energy and can lead to anxiety, depression, reduced decision-making ability, and impaired well-being.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

What Exactly Is Overthinking?

Overthinking can be broadly defined as repetitive, persistent, and unproductive thinking about negative experiences, thoughts, or possibilities (Kaiser et al., 2015). Although individuals sometimes believe they are problem-solving, overthinking does not produce action; instead, it focuses on analyzing, replaying, and imagining — without resolution.

Rumination

Rumination involves repeatedly analyzing mistakes, personal flaws, or negative outcomes. For example, replaying a conversation over and over, wondering what should have been said differently. Rumination becomes problematic when it leads to emotional distress instead of insight (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000).

Worry

Worry focuses on future danger or uncertainty: catastrophic predictions, fear of failure, and anticipation of worst outcomes. Excessive worry is a key feature of generalized anxiety disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Both rumination and worry are designed, evolutionarily, to help us solve problems and stay safe — yet they become harmful when they dominate mental life.

Why Does the Brain Overthink?

The brain is wired to prioritize risk, threat, and survival. From an evolutionary perspective, anticipating danger kept early humans alive. But in a modern world where daily threats are rarely life-or-death, this mechanism becomes misdirected, producing internal stress responses to non-dangerous issues like emails, deadlines, or interpersonal tension.

Neurochemical Looping

When we worry, stress hormones including cortisol and adrenaline are released, putting the body into alert. Cortisol increases vigilance and scanning for threats, but it also produces restlessness and physiological tension. The brain becomes conditioned to continue monitoring danger, keeping worry loops alive (Brosschot et al., 2006).

Additionally, dopamine — the neurotransmitter associated with reward — may reinforce rumination because analyzing problems creates an illusion of productivity, producing small bursts of reward even though no real solution is reached (Sweeney, 2019).

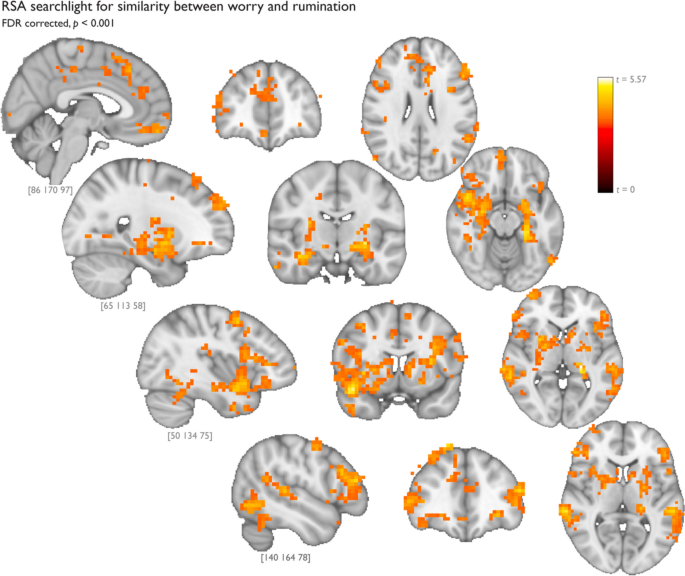

The Default Mode Network (DMN)

Neuroscientists have identified a brain network called the Default Mode Network (DMN) that becomes active when the mind is not focused on a task — such as when daydreaming or self-reflecting. Overactivation of the DMN is associated with rumination and depression (Hamilton et al., 2015). Individuals prone to overthinking show excessive DMN activation, meaning their brain defaults to inward self-focused thinking, often negative.

Cognitive Biases

Humans naturally exhibit:

-

Negativity bias: we pay more attention to threats than positives (Baumeister et al., 2001).

-

Catastrophic thinking: assuming worst outcomes.

-

Perfectionism: unrealistic expectations leading to fear of imperfection.

These patterns amplify overthinking by transforming minor problems into crises.

The Costs of Overthinking

The cost of overthinking it includes:

Emotional and Mental Health Consequences

Research shows strong links between overthinking, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Rumination predicts longer depressive episodes and increases the likelihood of relapse (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). Worry, similarly, increases physiological stress and anxiety symptoms.

Decision Paralysis

When overloaded with possibilities, the mind becomes unable to choose, a phenomenon known as analysis paralysis. People often delay decisions, avoid action, or endlessly research instead of committing. Studies indicate that more choices increase anxiety and decrease satisfaction (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000) — a modern problem intensified by technology and social comparison.

Reduced Productivity and Creativity

Overthinking prevents flow states and cognitive flexibility, key elements of problem solving and creativity. Constant mental pressure restricts working memory and attention, impairing effective reasoning (Eysenck & Calvo, 1992).

Relationship Strain

Overthinking causes individuals to interpret neutral events negatively, assume the worst intentions of others, or continuously seek reassurance, which can exhaust partners and friends.

How to Break the Cycle

Some ways to break this cycle include:

1. Externalize Thoughts

Writing or speaking thoughts aloud shifts them from looping internally to structured processing. Journaling interrupts rumination by engaging analytical regions of the brain and reducing emotional charge (Pennebaker & Chung, 2011). A short practice such as writing thoughts for five minutes daily creates psychological distance.

2. Take Action Rather Than Think More

Overthinking thrives in passivity. Even small behavioral steps reduce uncertainty and build momentum. Behavioral activation — taking action even without motivation — is one of the most effective treatments for depression (Martell et al., 2010).

3. Mindfulness and Grounding

Mindfulness meditation reduces DMN activity and lowers rumination and anxiety symptoms (Hamilton et al., 2015). Grounding exercises such as focusing on breath or sensory details anchor the mind in the present.

4. Limit Rumination Time

A strategy supported in cognitive-behavioral therapy is scheduling “worry time,” giving yourself 10-15 minutes each day to think through concerns, then intentionally stopping. Over time, the mind learns boundaries and reduces intrusive thinking (Borkovec et al., 1983).

5. Challenge Cognitive Distortions

Ask:

-

Is this thought a fact or a fear?

-

What evidence supports or contradicts it?

-

What would I tell a friend feeling this way?

This reframes assumptions into assessment rather than catastrophizing.

6. Reduce Information Overload

Constant comparison through social media worsens uncertainty and perfectionism. Limiting input quiets mental noise and restores clarity.

7. Self-Compassion

Research shows self-compassion significantly reduces rumination and promotes emotional resilience (Neff, 2011). Treating oneself with the same understanding given to a loved one interrupts cycles of self-criticism.

When Overthinking Becomes a Clinical Issue

Occasional overthinking is normal, but persistent, uncontrollable spiraling may signal generalized anxiety disorder, major depression, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, or trauma-related hypervigilance. Warning signs include:

-

inability to relax or sleep

-

physical symptoms (tension, headaches, stomach distress)

-

avoidance of tasks or decisions

-

intense self-criticism

In such cases, therapy (CBT, ACT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy) is highly effective and sometimes supported by medication when appropriate (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Conclusion

Overthinking is a mental habit that masquerades as problem solving but rarely produces solutions. Rooted in evolved survival systems, reinforced by neurochemical loops, and intensified by modern pressures, it traps individuals in cycles of worry and self-criticism. Yet the brain is adaptable: with intentional strategies — such as mindfulness, journaling, behavioral activation, and restructuring thoughts — it is entirely possible to retrain mental patterns. Freedom from overthinking doesn’t require eliminating thought, but redirecting it productively and compassionately.

Learning to step out of your head and into action, presence, and self-kindness can transform life from mental chaos into clarity and calm.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370.

Borkovec, T. D., Wilkinson, L., Folensbee, R., & Lerman, C. (1983). Stimulus control applications to the treatment of worry. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21(3), 247–251.

Brosschot, J. F., Gerin, W., & Thayer, J. F. (2006). The perseverative cognition hypothesis. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 75(3), 177–186.

Eysenck, M. W., & Calvo, M. G. (1992). Anxiety and performance: Attentional control theory. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 6(4), 367–385.

Hamilton, J. P., Farmer, M., Fogelman, P., & Gotlib, I. H. (2015). Depressive rumination and the brain. Biological Psychiatry, 78(4), 224–232.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995–1006.

Kaiser, B. N., Haroz, E. E., Kohrt, B. A., Bolton, P., Bass, J. K., & Hinton, D. (2015). “Thinking too much”: A systematic review of idioms of distress. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 170–183.

Martell, C. R., Dimidjian, S., & Herman-Dunn, R. (2010). Behavioral activation for depression: A clinician’s guide. Guilford Press.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 1–12.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424.

Sweeney, K. (2019). The reward of uncertainty. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(2), 224–243.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, November 28). Overthinking and 7 Ways to Break Its Cycle. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/overthinking-and-7-ways-to-break-its-cycle/