Every October, as pumpkins glow and shadows stretch longer, our fascination with ghosts, spirits, and haunted houses intensifies. Halloween offers the perfect excuse to flirt with fear — but beneath the cobwebs and costumes lies something deeper: the human mind’s incredible ability to create, perceive, and believe in the unseen.

Why do people feel “haunted”? Why do ordinary noises or flickering lights suddenly seem otherworldly at night? Psychology provides some fascinating answers. From sleep paralysis to perception errors and cultural influence, the feeling of being haunted reveals more about how our brains work than about any spirits that may linger.

Read More: Heuristics

A Haunting Begins in the Mind

Imagine waking in the middle of the night — unable to move, a crushing pressure on your chest, and a dark figure hovering nearby. Your heart races. You’re convinced something supernatural is happening.

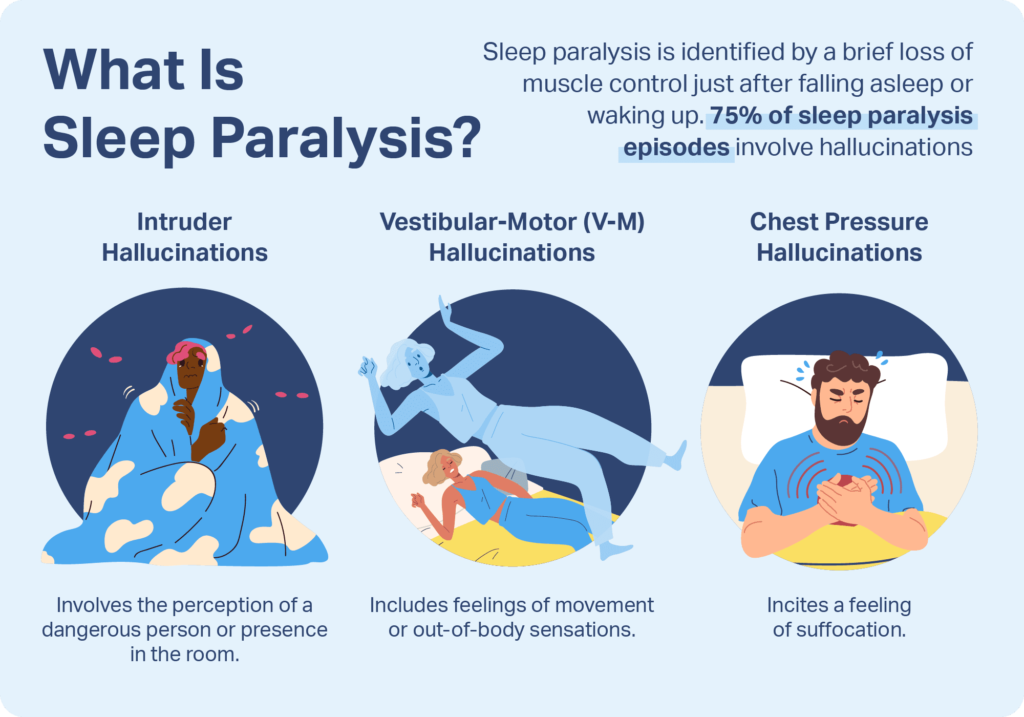

Psychologists call this sleep paralysis, a temporary state where you wake before your body exits REM sleep, leaving you paralyzed but conscious. During REM sleep, vivid dreams are common, and when parts of this dreaming state bleed into wakefulness, hallucinations of intruders or shadowy figures can occur (Lezak, 1995).

Jalal and Hinton (2015) explain that sleep paralysis often triggers a sensation of a “presence” in the room, which the frightened mind interprets according to cultural and personal beliefs — as a ghost, a demon, or even an alien. From a biological view, these experiences reflect a mismatch between the brain’s arousal system and motor control, not paranormal activity.

Studies also show that people with poor sleep quality report more frequent paranormal experiences (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). When we’re sleep-deprived or stressed, the brain’s ability to distinguish between dream imagery and real sensory input becomes blurred. Thus, many hauntings begin not in the graveyard but in our bedrooms — within the mechanics of the sleeping brain.

Pareidolia and Expectation

Even outside the dream world, our brains are prone to pareidolia — the tendency to see meaningful patterns in random stimuli. That face in the window or ghostly figure in the mist? It’s your brain’s pattern-recognition system doing its job a little too well (Anastasi & Urbina, 2005).

From an evolutionary standpoint, this bias was once useful. Mistaking a shadow for a predator was safer than the other way around. But during Halloween, when fear and suggestion are high, pareidolia turns creaking floors and moving curtains into signs of a spirit.

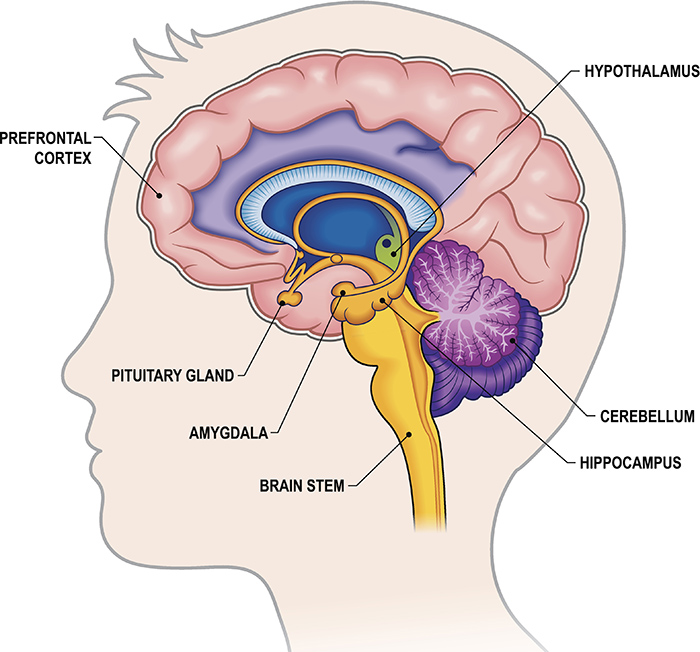

Barlow and Durand (1999) point out that fear heightens sensory vigilance. When the amygdala (the brain’s fear center) activates, perception becomes hypersensitive to threat cues. This means we’re more likely to interpret ambiguous sights and sounds as intentional — or malevolent. A flickering light becomes “a ghost trying to communicate,” not just faulty wiring.

The Power of Suggestion

Human perception is deeply shaped by suggestion. When we expect to see something — especially something frightening — we often do. Classic studies in abnormal psychology have shown that priming individuals with ghost-related cues increases their likelihood of reporting supernatural sensations (Sarason & Sarason, 2005).

This effect is amplified in group settings. In haunted houses or ghost tours, emotional contagion spreads rapidly — one person’s gasp or claim of seeing a shadow raises everyone’s arousal, making the group collectively misinterpret ordinary stimuli (Carson, Butcher, Mineka, & Hooley, 2007).

Such expectancy effects also explain why haunted environments feel so convincing. Dim lighting, temperature drops, and eerie sounds all prime the brain to search for explanations, and when logic fails, the supernatural fills the gap.

Wolman (1975) emphasized that belief systems act as cognitive filters; once an individual labels a situation as “haunted,” subsequent experiences are interpreted through that lens. Every creak becomes confirmation, not coincidence.

Cultural Beliefs and the Ghost Narrative

Not all hauntings look the same. Cultural context shapes how people interpret strange experiences. In Japan, it may be attributed to ancestral spirits; in India, to “bhoots” or “chudails”; in the West, to ghosts or demons. Despite these differences, the psychological experience — a sense of presence, pressure on the chest, or cold fear — is remarkably similar across societies (Kapur, 1995).

According to Sundberg, Winebarger, and Taplin (2002), culture supplies the “scripts” for how people interpret ambiguous sensations. A Western teenager influenced by horror films may describe “a ghost in the hallway,” while a Thai sleeper might blame “Phi Am,” a nocturnal spirit.

Halloween itself amplifies these cultural narratives. Media, storytelling, and ritual dress the environment in fear, increasing our readiness to perceive the extraordinary. The “haunting” thus becomes a shared psychological performance — a dance between expectation and imagination.

Why Haunted Experiences Feel So Real?

One of the most compelling aspects of ghostly encounters is their emotional intensity. Even after rational explanations, the fear remains vivid. This is because emotions influence perception as much as perception influences emotion.

Davison, Neal, and Kring (2004) describe this as emotion-perception feedback: when we feel fear, we perceive the world as more threatening, which in turn deepens our fear. In dark, ambiguous settings, the body’s physiological responses — pounding heart, cold sweat, tunnel vision — reinforce the sense of danger.

Additionally, once the brain’s limbic system (responsible for emotion and memory) is activated, experiences are encoded with heightened vividness (Taylor, 2006). This is why ghost experiences feel unforgettable — they’re literally burned into emotional memory circuits.

Neuropsychological research supports this. Lezak (1995) notes that hallucinations, especially those tied to emotional stress, activate similar brain regions as real sensory input. To the experiencer, the ghost is not imagined; it’s perceived.

The Role of Environment

Environmental factors can also play eerie tricks. Psychologists have identified low-frequency sound waves, known as infrasound, as a possible source of “haunted” sensations. These vibrations, often produced by wind or old machinery, can cause feelings of unease, anxiety, and even visual distortions (Kellerman & Burry, 1981).

Temperature fluctuations, carbon monoxide leaks, and electromagnetic fields can also induce dizziness or hallucinations, which people often interpret as paranormal. When combined with the expectation of haunting, these sensations form a powerful illusion.

Thus, the architecture of haunted houses — narrow hallways, flickering candles, irregular sounds — capitalizes on how our sensory systems misfire under stress (Alloy, Riskind, & Manos, 2005). The thrill we feel is both biological and psychological.

Why We Want to Believe

Despite scientific explanations, the allure of ghosts persists. Humans are storytelling creatures, driven by meaning-making. Believing in spirits helps people make sense of loss, mystery, and mortality (Brannon & Feist, 2007).

Nolen-Hoeksema (2004) argues that paranormal beliefs serve emotional regulation — offering comfort against uncertainty and death anxiety. Halloween’s popularity, then, isn’t just about scaring ourselves; it’s about confronting fear in a safe, playful way.

As Sarason and Sarason (2005) observed, fear rituals like Halloween allow society to externalize internal anxieties, turning existential dread into entertainment. We “play” with fear to master it.

How to Calm a Haunted Mind

For those genuinely frightened by nighttime presences or ghostly sensations, psychological tools can help:

- Improve sleep hygiene. Keep consistent sleep schedules and avoid sleeping on your back — the position most associated with sleep paralysis (Lezak, 1995).

- Reframe the experience. Replace “there’s a ghost” with “my brain is misfiring between dream and wake.” This reduces panic and restores control (Anastasi & Urbina, 2005).

- Grounding techniques. Focus on breathing, move your toes or fingers to regain body control, and note your surroundings aloud.

- Manage stress. Anxiety heightens sensory misperception. Mindfulness and relaxation lower physiological arousal, reducing haunting sensations (Taylor, 2006).

Conclusion

Halloween celebrates our fascination with fear — and fear is, above all, a psychological experience. The ghosts we see, the chills we feel, and the presences we sense are not merely supernatural; they are reflections of a mind finely tuned to detect danger, meaning, and mystery.

So when shadows flicker this Halloween, remember: it’s your brain doing what it does best — finding patterns, telling stories, and keeping you safe. The haunted mind, after all, is just another expression of the beautifully complex human psyche.

References

Alloy, L. B., Riskind, J. H., & Manos, M. J. (2005). Abnormal psychology: Current perspectives (9th ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill.

Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (2005). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (1999). Abnormal psychology (2nd ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Brannon, L., & Feist, J. (2007). Introduction to health psychology. Thomson Wadsworth.

Carson, R. C., Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2007). Abnormal psychology (13th ed.). Pearson Education India.

Davison, G. C., Neal, J. M., & Kring, A. M. (2004). Abnormal psychology (9th ed.). Wiley.

Jalal, B., & Hinton, D. E. (2015). Sleep paralysis among Egyptian college students: Association with anxiety symptoms (Study reference discussed in context).

Kapur, M. (1995). Mental health of Indian children. Sage Publications.

Kellerman, H., & Burry, A. (1981). Handbook of diagnostic testing: Personality analysis and report writing. Grune & Stratton.

Lezak, M. D. (1995). Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford University Press.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2004). Abnormal psychology (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Sarason, I. G., & Sarason, B. R. (2005). Abnormal psychology. Dorling Kindersley.

Sundberg, N. D., Winebarger, A. A., & Taplin, J. R. (2002). Clinical psychology: Evolving theory, practice, and research. Prentice-Hall.

Taylor, S. (2006). Health psychology. Tata McGraw-Hill.

Wolman, B. B. (1975). Handbook of clinical psychology. McGraw-Hill.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 31). The Psychology of Feeling Haunted and 4 Important Ways to Calm a Haunted Mind. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/psychology-of-feeling-haunted/