Introduction

Childhood is ideally a time of play, exploration, and care. Yet for many individuals, it becomes a period of responsibility, emotional labor, and reversed roles. These children act as caretakers, confidants, or problem-solvers for their parents. Psychologists call this process parentification—a term that describes when a child assumes adult-like duties within the family system. While some degree of responsibility can nurture maturity, chronic or inappropriate parentification can lead to profound emotional and developmental consequences.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

Defining Parentification

Parentification occurs when a child is expected to fulfill roles or responsibilities normally carried by a parent. Jurkovic (1997) defined it as “the distortion of the parent-child relationship such that the child sacrifices his or her own needs to take care of the instrumental or emotional needs of the parent.” This inversion of roles disrupts the natural caregiving hierarchy within families.

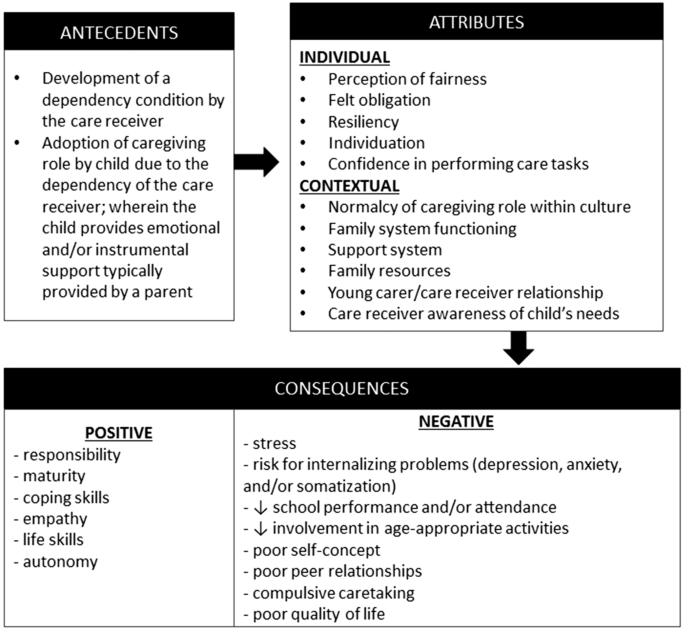

Two primary forms of parentification are typically identified (Hooper, 2007):

- Instrumental Parentification: The child takes on practical responsibilities—cooking, cleaning, caring for siblings, or managing household duties.

- Emotional Parentification: The child becomes an emotional support system for one or both parents, often serving as a confidant, mediator, or even therapist.

While occasional responsibility can promote competence, parentification becomes harmful when it is chronic, developmentally inappropriate, or accompanied by emotional neglect.

Causes and Family Context

Parentification commonly arises in families under significant stress or dysfunction. When parents struggle with physical illness, mental health issues, substance abuse, or economic instability, children may feel compelled—or be expected—to “step up” (Chase, 1999). Divorce, single parenting, or cultural expectations emphasizing filial duty can also increase the likelihood of role reversal.

Family systems theory explains parentification as a disruption of generational boundaries (Bowen, 1978). The child’s caretaking functions compensate for a parental deficit but simultaneously interfere with the child’s own developmental needs. For example, a daughter comforting a depressed mother after marital conflict assumes an emotional role that exceeds her capacity. Over time, this dynamic may normalize dysfunction and inhibit emotional autonomy.

The Psychological Mechanisms Behind Parentification

From a psychological standpoint, parentification creates internal conflicts related to identity and self-worth. Hooper (2007) suggested that parentified children often develop an “external locus of self,” where their sense of value depends on serving others. They may equate love with caretaking, viewing their worth as conditional upon meeting others’ needs.

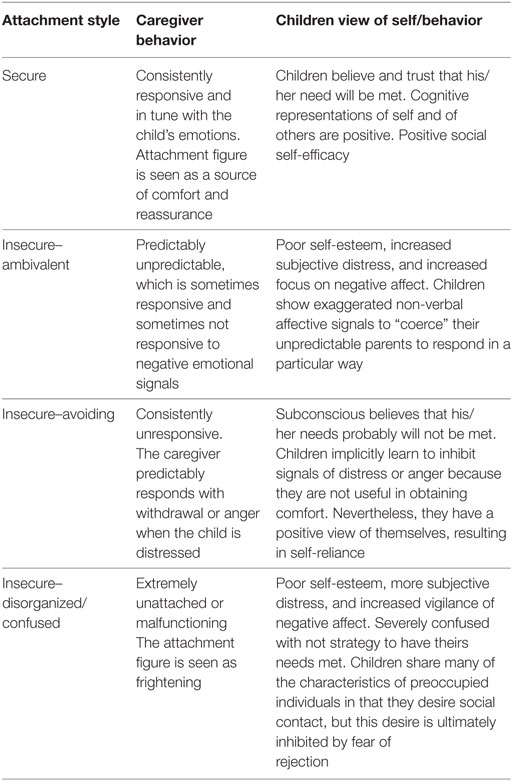

Attachment theory provides another lens. When parents rely on children for emotional support, the traditional secure base is compromised (Bowlby, 1988). The child learns to suppress vulnerability and adopt a pseudo-adult stance, which can impede secure attachment formation. As adults, such individuals may struggle with boundaries, experience guilt when prioritizing themselves, or attract partners who replicate the original dynamic.

Neuroscience research also supports the stress-related consequences of role reversal. Chronic caregiving responsibilities in childhood can elevate cortisol levels, contributing to hypervigilance and emotional dysregulation (Hooper et al., 2011). Thus, parentification is not merely an emotional burden—it may also manifest physiologically.

Emotional and Behavioral Outcomes

The effects of parentification vary depending on intensity, duration, and the child’s temperament. Research identifies both maladaptive and adaptive outcomes.

Negative Outcomes

- Emotional Distress and Burnout: Parentified children report higher levels of anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms than their non-parentified peers (Hooper et al., 2008).

- Guilt and Shame: Many internalize guilt for failing to “save” their parents or siblings, leading to chronic feelings of inadequacy.

- Difficulty with Boundaries: Adults who experienced parentification may overextend themselves in relationships, becoming caretakers or “fixers” (Jurkovic, 1997).

- Suppressed Identity Development: The need to meet family needs prematurely can prevent self-exploration and identity formation during adolescence (Chase, 1999).

- Risk of Intergenerational Transmission: Studies show that parentified individuals may unintentionally replicate similar dynamics when they become parents, perpetuating cycles of emotional inversion (Macfie et al., 2005).

Positive or Adaptive Outcomes

Not all outcomes are negative. Some research suggests limited parentification can foster resilience, empathy, and problem-solving skills (Earley & Cushway, 2002). When the child’s contribution is acknowledged and supported, they may develop strong interpersonal competence. However, these adaptive effects tend to occur when parentification is temporary and accompanied by emotional validation.

Parentification in Cultural Context

Parentification is not always perceived negatively across cultures. In collectivist societies, children often take active roles in supporting family welfare. Cultural norms may frame these contributions as honorable rather than pathological (Hooper et al., 2011). However, even within such frameworks, the distinction lies in choice and support. Voluntary responsibility that respects the child’s developmental stage differs profoundly from enforced caregiving due to parental incapacity. When responsibility turns into obligation without emotional reciprocity, the outcome remains psychologically taxing.

Parentification and Adult Relationships

Adults who experienced parentification often carry internalized caretaker roles into relationships. They may attract emotionally unavailable partners or feel compelled to “fix” others (Jurkovic, 1997). This pattern stems from learned self-neglect; love becomes synonymous with service. Conversely, some individuals avoid intimacy altogether, fearing dependency or engulfment.

Therapeutically, addressing parentification involves exploring these patterns through attachment-informed approaches. Recognizing that one’s worth does not depend on caregiving is essential for emotional freedom.

Healing and Recovery

Healing from parentification requires both emotional insight and behavioral change. Psychologists recommend several strategies:

- Acknowledgment: The first step is naming the experience. Recognizing that role reversal occurred validates the child’s burden (Hooper, 2014).

- Grieving Lost Childhood: Many must mourn the carefree experiences they were denied. This process helps integrate unmet needs.

- Establishing Boundaries: Learning to differentiate between helping and over-functioning restores balance in relationships.

- Therapy and Reparenting: Cognitive-behavioral, psychodynamic, and inner-child approaches can aid individuals in reestablishing internal safety and self-compassion (Wells & Jones, 2000).

- Reclaiming Play: Engaging in creativity and leisure activities reconnects adults with the child-self that had to “grow up too fast.”

For families currently facing parentification risks—such as single-parent or high-stress households—community support and family therapy can prevent long-term harm.

Professional and Societal Implications

For mental health professionals, identifying parentification is critical to effective treatment. Counselors should assess not only trauma history but also family role patterns. Hooper et al. (2008) suggested using the Parentification Questionnaire (PQ) to measure the degree of emotional and instrumental role reversal.

Schools and social systems can also play preventive roles. Teachers observing “overly mature” children should look beyond surface competence to possible family stressors. Early intervention and supportive mentorship can buffer negative outcomes.

Societally, acknowledging parentification challenges cultural myths that glorify “strong” or “self-sufficient” children. Strength in childhood often conceals emotional deprivation. Recognizing this distinction allows for more compassionate educational and policy responses.

Conclusion

Parentification represents a profound reversal of the natural caregiving hierarchy. Though it may yield maturity and competence, the hidden emotional toll can last well into adulthood. Children who must parent their parents sacrifice spontaneity for stability and self-care for survival. Understanding the nuances of parentification—its causes, contexts, and outcomes—enables healing, empathy, and systemic change.

Healing begins when adults who were once parentified learn to give themselves the same care they once gave others. In doing so, they finally allow the inner child to rest.

References

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. Jason Aronson.

Chase, N. D. (1999). Burdened children: Theory, research, and treatment of parentification. Sage.

Earley, L., & Cushway, D. (2002). The parentified child. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104502007002005

Hooper, L. M. (2007). The application of attachment theory and family systems theory to the phenomena of parentification. The Family Journal, 15(3), 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480707301290

Hooper, L. M., Doehler, K., Jankowski, P. J., & Tomek, S. (2011). Patterns of self-reported parentification and mental health symptoms among college students: Validation of the Parentification Questionnaire–Youth. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 42(2), 210–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-010-0212-5

Hooper, L. M., Marotta, S. A., & Lanthier, R. P. (2008). Predictors of growth and distress following childhood parentification: A retrospective exploratory study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17(5), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-007-9184-8

Hooper, L. M. (2014). Parentification. In C. J. McClure & M. T. Foster (Eds.), Encyclopedia of emerging adulthood: Development, management, and applications (pp. 485–487). Greenwood.

Jurkovic, G. J. (1997). Lost childhoods: The plight of the parentified child. Brunner/Mazel.

Macfie, J., Houts, R. M., Pressel, A., & Cox, M. J. (2005). Pathways from child maltreatment to adult psychological adjustment: The role of parentification. Development and Psychopathology, 17(3), 529–549. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579405050256

Wells, M., & Jones, R. (2000). Childhood parentification and shame-proneness: A preliminary study. American Journal of Family Therapy, 28(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/019261800261815

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,044 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 24). What is Parentification and 5 Important Negative Outcomes of It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/parentification-negative-outcomes/