Introduction

In a world that loves categories and labels, few dichotomies are as popular as that of introverts and extraverts. Social media, self-help books, and personality tests often force people to pick a side: are you the quiet thinker or the social butterfly? However, most individuals do not neatly fit either category. Many people display a blend of both—sociable yet reflective, outgoing yet independent. These individuals are known as ambiverts.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

Defining Ambiversion

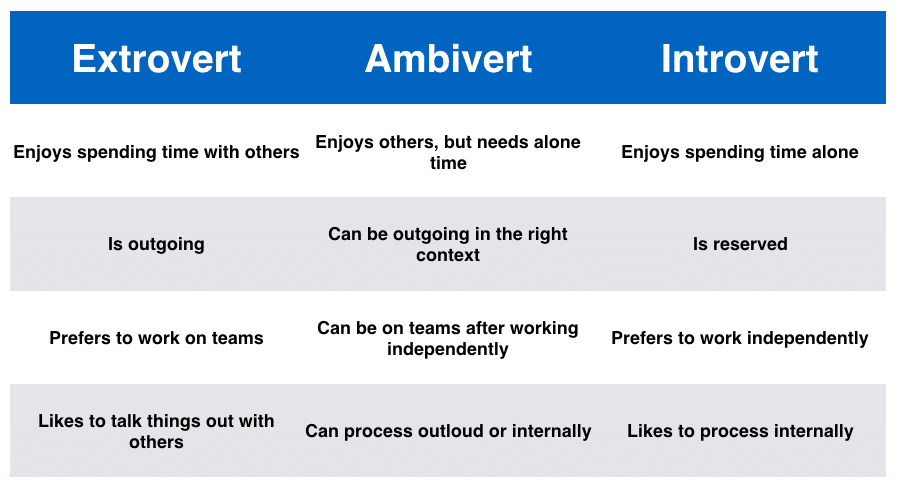

The term ambivert refers to someone who demonstrates both introverted and extraverted traits depending on the situation. Psychologist Edward S. Conklin first used the term in the 1920s to describe individuals whose behaviors and attitudes lie between the two extremes (Conklin, 1923). Modern personality theory acknowledges that introversion and extraversion exist on a continuum rather than as a binary trait (Costa & McCrae, 1992). In other words, personality is not a rigid category but a flexible spectrum.

Ambiverts enjoy social interactions but also need solitude to recharge. They may thrive at a party one night and prefer quiet reading the next day. As Grant (2013) explained, ambiverts possess a balance of assertiveness and receptivity, enabling them to adapt to the demands of diverse environments. This adaptability is one of the defining strengths of ambiversion.

Core Traits of Ambiverts

Research suggests that ambiverts share specific cognitive and behavioral patterns that distinguish them from those on either end of the introversion–extraversion spectrum.

- Adaptability: Ambiverts can shift their behavior based on situational cues. They are comfortable engaging socially when necessary but also value introspection when alone (Wilt & Revelle, 2009).

- Balanced Energy: While introverts gain energy from solitude and extraverts from social interaction, ambiverts tend to maintain stable energy levels across settings (Fleeson & Gallagher, 2009).

- Empathic Listening: Because ambiverts alternate between talking and listening, they often excel in communication that requires empathy and perspective-taking (Grant, 2013).

- Contextual Intelligence: Ambiverts tend to exhibit high social sensitivity. They can “read the room” and adjust tone, intensity, and engagement levels accordingly (Cain, 2012).

This dynamic balance gives ambiverts a certain psychological flexibility—a concept linked to emotional intelligence and social competence.

Ambiverts in the Workplace

The workplace is one domain where ambiversion shows clear advantages. Traditionally, extroverts were perceived as more successful in leadership and sales because of their outgoing personalities and verbal confidence. However, research challenges this assumption. In a landmark study, Grant (2013) found that ambiverts outperformed both introverts and extroverts in sales performance. The reason? Ambiverts were assertive enough to persuade yet reserved enough to listen to customer needs.

Similarly, leadership studies show that effective leaders are often those who know when to speak and when to listen. Extraverted leaders may dominate discussions, while introverted ones may hesitate to voice ideas. Ambiverts, by contrast, exhibit situational awareness, which allows them to adapt their approach to team dynamics (Rego et al., 2016). This adaptability supports more collaborative and inclusive leadership.

Moreover, ambiverts are less likely to experience the social fatigue that introverts face in group settings and less likely to overlook details that extraverts sometimes miss (Laney, 2002). In a post-pandemic world that values flexibility—such as hybrid work models and cross-functional collaboration—ambiverts’ ability to shift between solitude and sociability becomes a critical skill.

Ambiverts and Relationships

Ambiverts’ balanced nature also influences how they connect with others. They can enjoy deep, one-on-one conversations typical of introverts while also engaging comfortably in group activities. This makes them adaptable partners and friends. However, ambiverts may sometimes feel misunderstood because others expect consistency in social behavior. A friend may assume the ambivert is always outgoing, not realizing they may need solitude after intense socializing.

Communication researchers suggest that ambiverts maintain stronger relational satisfaction because they can both express themselves and listen actively (Ashton & Lee, 2007). They also tend to manage conflict constructively, balancing assertiveness with diplomacy. This duality helps sustain relationships in personal and professional contexts.

Challenges of Being an Ambivert

While ambiversion has advantages, it also presents unique challenges:

- Identity Ambiguity: Because ambiverts fluctuate between social modes, they sometimes struggle to define themselves. This can lead to self-doubt or a feeling of not “fitting in” (Laney, 2002).

- Energy Mismanagement: Ambiverts may overcommit socially, misjudging how much interaction they can handle before exhaustion sets in.

- Inconsistent Perception: Colleagues or friends may perceive ambiverts as inconsistent—outgoing one day and reserved the next—leading to misunderstandings.

- Neglect of Personal Needs: Their ability to adapt can cause ambiverts to prioritize others’ comfort over their own, especially in social or work settings (Cain, 2012).

Despite these difficulties, self-awareness can help ambiverts manage their flexibility without losing authenticity.

Ambiversion and Mental Health

Psychologically, ambiverts may experience more emotional equilibrium than individuals at the extremes of introversion and extraversion. Because they are not chronically overstimulated or under-stimulated, they maintain greater mood stability (Wilt & Revelle, 2009).

However, the ability to oscillate between modes also means that ambiverts must regularly self-regulate. Failing to honor internal needs—such as rest after social exertion—can lead to burnout or irritability. Practicing mindfulness and self-monitoring can help ambiverts maintain balance.

There is also a link between ambiversion and emotional intelligence (EQ). Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso (2008) note that individuals high in EQ demonstrate self-awareness and social adaptability, both of which are traits found in ambiverts. Thus, cultivating emotional intelligence can enhance ambiverts’ natural strengths.

Why the Ambivert Advantage Matters

The ambivert advantage extends beyond personality—it represents an adaptive strategy in a world that demands flexibility. The 21st-century environment values multitasking, collaboration, and digital communication across diverse platforms. Ambiverts’ ability to toggle between introspection and expression enables them to thrive in such complexity.

Social psychologist Brian Little (2014) introduced the concept of “free traits,” which suggests people can act out of character temporarily to achieve goals. Ambiverts, by nature, may embody this fluidity more easily. They can present as extraverts in public-facing roles and as introverts in analytical tasks, without feeling inauthentic. This behavioral range gives them resilience in changing environments.

Developing Ambivert Skills

While personality is partially innate, behavioral flexibility can be cultivated. Here are some strategies to harness ambivert strengths:

- Self-Monitoring: Track your energy after social or solitary activities. Identify which environments recharge or deplete you.

- Adaptive Communication: Practice alternating between active listening and assertive speaking in conversations.

- Boundary Setting: Learn to decline social invitations when overstimulated, even if others expect engagement.

- Intentional Solitude: Schedule alone time to restore balance, especially after extended social periods.

- Mindful Leadership: When managing others, consciously balance input and output—listen first, then contribute.

These habits enhance self-regulation and reinforce the benefits of ambiversion.

Conclusion

Ambiverts represent the majority of people, even if they seldom receive recognition. In reality, human personality is fluid, and situational demands shape how we express ourselves. Rather than asking whether one is introverted or extraverted, the more accurate question may be, “How flexibly can I respond to different contexts?”

Embracing ambiversion means valuing both quiet introspection and active engagement. It means realizing that strength often lies not in extremes but in equilibrium. In a world that prizes loudness or solitude, the ambivert quietly excels by mastering both.

References

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868306294907

Cain, S. (2012). Quiet: The power of introverts in a world that can’t stop talking. Crown.

Conklin, E. S. (1923). Introduction to abnormal psychology. Appleton-Century.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

Fleeson, W., & Gallagher, P. (2009). The implications of Big Five standing for the distribution of trait manifestation in behavior: Fifteen experience-sampling studies and a meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1097–1114. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016786

Grant, A. M. (2013). Rethinking the extraverted sales ideal: The ambivert advantage. Psychological Science, 24(6), 1024–1030. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612463706

Laney, M. O. (2002). The introvert advantage: How to thrive in an extrovert world. Workman Publishing.

Little, B. R. (2014). Me, myself, and us: The science of personality and the art of well-being. PublicAffairs.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2008). Emotional intelligence: New ability or eclectic traits? American Psychologist, 63(6), 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.6.503

Rego, A., Sousa, F., Marques, C., & Cunha, M. P. (2016). Authentic leadership promoting employees’ psychological capital and creativity. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3738–3748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.03.005

Wilt, J., & Revelle, W. (2009). Extraversion. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 27–45). Guilford Press.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,043 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 23). Who are Ambiverts and Learn 4 Important Traits of Them. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/ambiverts-traits/