Why do your palms sweat before a big presentation?

Why does hearing an old song suddenly make your eyes water?

And why can anger make your heart race while love makes it slow down?

Emotions are among the most fascinating—and complex—features of the human experience. They color every thought, decision, and memory, shaping how we interact with the world and with each other. But behind every laugh, tear, and shiver lies a deeply coordinated dance of brain chemistry and neural signaling.

This article explores how emotions are processed in the brain, what science has revealed about the “emotional brain,” and why understanding our feelings might be the key to understanding ourselves.

Read More: Emotional SOS

What Are Emotions, Really?

Emotions are more than fleeting moods—they’re coordinated psychological and physiological responses that help us adapt to our environment (Ekman, 1992).

They serve as a built-in survival mechanism: fear alerts us to danger, joy reinforces rewarding behaviors, and sadness can signal a need for help or rest.

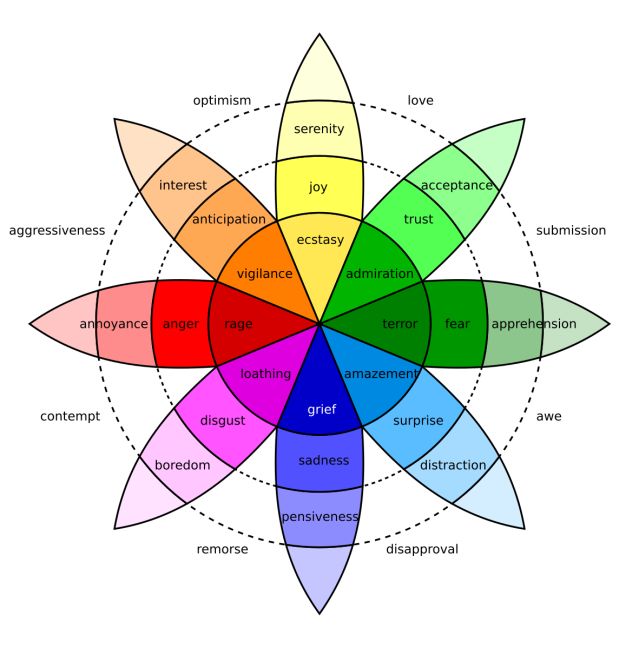

Paul Ekman’s research identified six “basic emotions” shared across cultures: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust (Ekman, 1992). These emotions are expressed similarly in people worldwide, suggesting deep biological roots.

The Emotional Brain

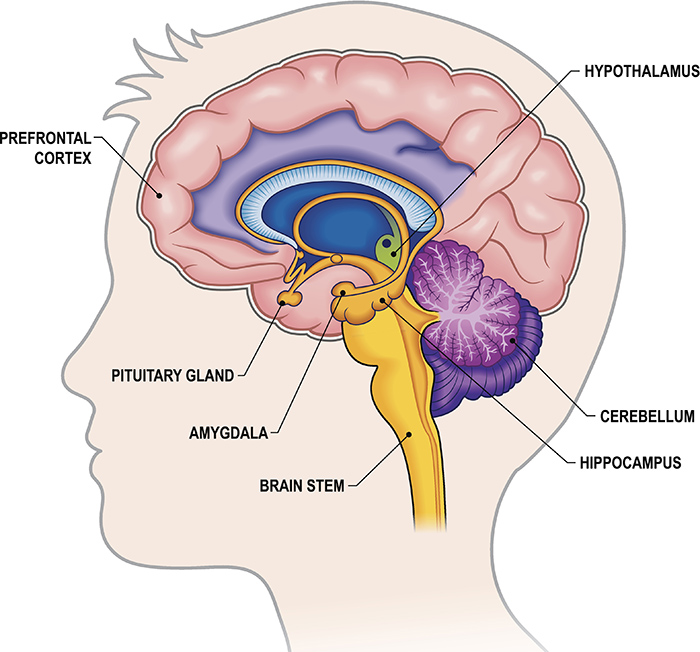

The brain doesn’t have a single “emotion center.” Instead, emotions emerge from interactions among several brain regions, collectively known as the limbic system. Key structures include:

-

Amygdala – Detects emotional significance, especially fear and threat.

-

Hippocampus – Links emotions to memories and context.

-

Hypothalamus – Triggers physiological responses (like increased heart rate).

-

Prefrontal Cortex – Regulates emotions, decision-making, and impulse control.

-

Insula – Processes bodily sensations that accompany emotions, like gut feelings.

Each emotion involves a unique combination of these brain regions working in harmony—or sometimes, in conflict.

1. The Amygdala

If the brain had an emotional “fire alarm,” it would be the amygdala. Located deep within the temporal lobe, the amygdala rapidly evaluates sensory input for potential threats.

When danger is detected, it activates the hypothalamus, setting off the fight-or-flight response—your heart races, muscles tense, and adrenaline floods the system (LeDoux, 1996).

This reaction occurs even before you consciously recognize the threat. That’s why you might jump at a sudden noise before realizing it’s just the wind. The amygdala acts first; your rational brain catches up later.

Interestingly, the amygdala doesn’t just process fear. It also helps evaluate positive stimuli, like recognizing a loved one’s face or feeling excitement about a reward (Murray, 2007).

2. The Prefrontal Cortex

If the amygdala is the emotional accelerator, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) is the brake. Located in the front part of the brain, the PFC helps us interpret and manage emotional impulses.

It’s what allows you to take a deep breath instead of shouting during an argument or to comfort a friend instead of panicking during a crisis.

Neuroscientist Richard Davidson (2000) found that the left PFC is associated with approach-related emotions like joy and interest, while the right PFC is linked to withdrawal emotions like fear and sadness.

When the PFC is functioning properly, it balances emotion and reason. When it’s underdeveloped (as in children) or impaired (due to stress or injury), emotions can become overwhelming.

3. The Hippocampus

Ever wondered why emotional memories feel stronger than neutral ones? You can thank the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure responsible for forming and retrieving memories.

The hippocampus works closely with the amygdala to tag emotional significance to experiences (Phelps, 2004). For instance, you might vividly remember your first heartbreak or the joy of a childhood birthday party.

This connection explains why trauma can leave such lasting imprints—and why recalling emotional events can reawaken the feelings associated with them.

4. The Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus acts as the bridge between the mind and the body. Once the amygdala signals a threat or emotional cue, the hypothalamus triggers physical reactions—releasing hormones like adrenaline or cortisol, changing heart rate, and adjusting body temperature (Carlson, 2013).

These physiological changes are what make emotions feel physical. Fear quickens the pulse; embarrassment makes us blush; love releases oxytocin and dopamine, creating warmth and bonding sensations (Feldman, 2017).

In essence, the hypothalamus translates emotional signals into bodily experiences.

5. The Insula

The insula, buried deep within the cerebral cortex, helps us interpret internal bodily states. It’s responsible for those “gut feelings” or intuitive sensations that accompany emotion (Craig, 2009).

For example, when you feel disgust, the insula activates both the perception and the physical response—such as nausea or recoil. Studies show that the insula is also crucial for empathy, as it allows us to “feel” others’ emotions through bodily resonance (Singer et al., 2004).

The Role of Neurotransmitters and Hormones

Behind every emotional state is a biochemical symphony.

- Dopamine fuels pleasure, reward, and motivation.

- Serotonin regulates mood and social behavior.

- Oxytocin promotes bonding, trust, and love.

- Adrenaline and cortisol prepare the body for action.

These neurotransmitters and hormones influence not only how we feel but also how long those feelings last. Chronic imbalances—like low serotonin or prolonged cortisol—can contribute to mood disorders such as depression or anxiety (Mayo Clinic, 2022).

Emotional Processing in Real Time

When you experience an emotional event, your brain processes it in three general stages:

- Appraisal – The amygdala and sensory cortices rapidly evaluate stimuli for emotional significance.

- Physiological Response – The hypothalamus activates bodily reactions through the autonomic nervous system.

- Regulation and Reflection – The prefrontal cortex interprets and modulates the emotion, allowing you to choose an appropriate response.

This process happens in milliseconds, creating a seamless flow between feeling and action. It’s what enables you to smile when you see a friend or flinch when something startles you.

Emotion and Decision-Making

Far from being irrational, emotions are essential for sound decision-making. Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio (1994) found that people with damage to emotion-related brain regions could think logically but struggled to make even simple choices.

Emotions provide a kind of “somatic marker”—a bodily signal that helps weigh options and predict consequences. Without them, decisions become cold, endless calculations with no sense of urgency or meaning.

So, emotion doesn’t cloud judgment—it refines it.

The Cultural Layer

While biology provides the foundation, culture shapes how emotions are expressed and interpreted.

Some cultures encourage open emotional expression (e.g., Southern Europe, Latin America), while others value restraint and composure (e.g., East Asia). Research shows that these norms can even influence brain activation patterns during emotional experiences (Matsumoto et al., 2008).

In short, our brains may be wired for emotion, but society teaches us when and how to show it.

Conclusion

Emotions are not random bursts of feeling; they are finely tuned signals that help us survive, connect, and thrive.

From the lightning-fast reaction of the amygdala to the careful reasoning of the prefrontal cortex, our brains constantly balance instinct and insight. Every heartbeat, every smile, every tear is the result of this intricate biological choreography.

Understanding how emotions are processed in the brain doesn’t make them less mysterious—it makes them even more extraordinary. Because in the end, to understand emotion is to understand what it means to be human.

References

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., & Salovey, P. (2019). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 88–103.

Carlson, N. R. (2013). Physiology of behavior (11th ed.). Pearson.

Craig, A. D. (2009). How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(1), 59–70.

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Davidson, R. J. (2000). Affective style, psychopathology, and resilience: Brain mechanisms and plasticity. American Psychologist, 55(11), 1196–1214.

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6(3–4), 169–200.

Feldman, R. (2017). The neurobiology of human attachments. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(2), 80–99.

LeDoux, J. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Simon & Schuster.

Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., & Nakagawa, S. (2008). Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(6), 925–937.

Mayo Clinic. (2022). Depression (major depressive disorder). Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Murray, E. A. (2007). The amygdala, reward, and emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(11), 489–497.

Phelps, E. A. (2004). Human emotion and memory: Interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 14(2), 198–202.

Singer, T., Seymour, B., O’Doherty, J., Kaube, H., Dolan, R. J., & Frith, C. D. (2004). Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science, 303(5661), 1157–1162.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, October 15). How Emotions Are Processed in the Brain and 5 Important Parts Involved In It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/emotions-are-processed-in-the-brain/