Introduction

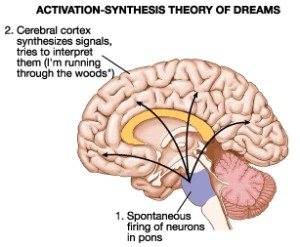

On any given night, you might find yourself flying across a neon city, walking barefoot on an endless staircase, or arguing with a teacher you haven’t seen since high school. The dreamscape is a strange theatre—sometimes comic, sometimes tragic, often baffling. Dreams intrigue us because they resist neat explanation. Are they nothing more than random neural sparks (Hobson & McCarley, 1977)? Or are they encoded messages, riddles crafted by the unconscious mind to be decoded like mythic stories?

Carl Jung once wrote, “The dream is the small hidden door in the deepest and most intimate sanctum of the soul” (Jung, 1964, p. 33). Through that door emerges not only archetypal figures and repressed emotions, but also the personal narrator that each of us becomes. To dream, then, is to practice being human—to rehearse stories of who we are, who we fear to be, and who we may yet become.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

The Birth of Dream Psychology

1. Freud

Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (1900/2010) changed everything. Before Freud, dreams were treated either as divine omens or trivial nonsense. Freud argued they were disguised expressions of unconscious wishes, particularly repressed sexual or aggressive drives.

For Freud, every dream had a manifest content (the literal storyline) and a latent content (the hidden meaning). A dream about climbing a staircase, he suggested, might symbolize sexual desire. The bizarreness of dreams was explained by the “censorship” of the unconscious, which disguised raw impulses in symbolic form.

This framework was criticized for being overly reductionist (Foulkes, 1985). Still, Freud made a radical claim: dreams are narratives of desire, not meaningless noise.

2. Jung

Carl Jung, initially Freud’s protégé, expanded the stage. Where Freud saw wish-fulfillment, Jung saw mythological dramas enacted by archetypes—the Hero, the Shadow, the Anima/Animus. For Jung, dreams were a conversation between the conscious ego and the collective unconscious (Jung, 1968).

For example:

-

Dreaming of a dark figure → confrontation with the Shadow.

-

Dreaming of guiding animals → symbolic wisdom from the Self.

-

Dreaming of circular patterns (mandalas) → movement toward psychic wholeness.

Jung emphasized that dreams were not puzzles to be solved but stories to be lived into. He noted: “The dream is a theater in which the dreamer is himself the scene, the player, the prompter, the producer, and the critic” (Jung, 1948/1966, p. 161).

Narrative Psychology and the Dreaming Self

Narrative psychology proposes that humans construct identity through story (McAdams, 1993). We do not merely live events—we interpret them, narrate them, and stitch them into coherent autobiographies.

Dreams, in this sense, are draft stories of the self, experiments in narrative. Just as we retell childhood events to define our identities, we “dream” fragments that anticipate, reframe, or resist our life stories.

Dreams as Narrative Practice

Research in dream studies shows that most dreams have a narrative structure: characters, settings, conflicts, and resolutions (Domhoff, 2017). Dreams may not be novels, but they are rarely static images. Instead, they are mini-narratives, albeit nonlinear and surreal.

Narrative psychologists suggest that dreams can function like first drafts of life stories—test runs for identity. For example, a college student dreaming of taking an exam unprepared may not simply reflect anxiety but a deeper narrative: “I fear I am not ready for adulthood.”

Anthropology of Dreaming

In Australian Aboriginal traditions, “Dreamtime” refers to the primordial time when ancestral beings shaped the world. Dreams are not mere personal fictions but bridges to sacred reality (Stanner, 1979).

In the Upanishads, dreaming is one of the four states of consciousness (alongside waking, deep sleep, and transcendence). The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (c. 700 BCE) declares: “When one dreams, he becomes the creator of his own world.” This view anticipates narrative psychology: the dreamer as myth-maker.

For the Greeks, dreams were messages from gods (Artemidorus, 2nd century CE). Temples of Asclepius practiced dream incubation, where people slept in sacred spaces hoping for healing dreams.

Across cultures, dreams were treated not as private nonsense but as meaning-making myths embedded in cosmic and communal stories.

Dreams as Therapy and Self-Authorship

Narrative therapy (White & Epston, 1990) encourages people to “re-author” their life stories. Dreams provide raw material for this. Dream journaling, for example, lets individuals identify recurring themes and integrate them consciously.

Lucid dreaming research (LaBerge, 1985) shows we can even “rewrite” dreams while dreaming—transforming nightmares into healing myths.

Philosophers have long mused on dreams:

-

Plato worried dreams unleash irrational desires (Republic, Book IX).

-

Descartes used dreams to doubt reality itself.

-

Indian Vedanta suggests waking life is itself a dream of Brahman.

Existentialists too weighed in. Sartre argued that dreams reveal our radical freedom: even asleep, consciousness projects worlds (Sartre, 1943/1992).

Dreams, then, are not just personal myths—they are philosophical provocations.

Conclusion

Dreams may never fully reveal their secrets. But through Freud’s repressions, Jung’s archetypes, narrative psychology’s storytelling self, and neuroscience’s REM models, a picture emerges: dreams are personal myths.

They are drafts of identity, mythic rehearsals of fear and hope, symbolic bridges between biology and culture. Just as myths tell societies who they are, dreams tell individuals who they are becoming.

When you next wake from a strange dream, consider: perhaps you did not just dream a story. Perhaps the story dreamed you.

References

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. Princeton University Press.

Domhoff, G. W. (2017). The emergence of dreaming: Mind-wandering, embodied simulation, and the default network. Oxford University Press.

Foulkes, D. (1985). Dreaming: A cognitive-psychological analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Freud, S. (2010). The interpretation of dreams (J. Strachey, Trans.). Basic Books. (Original work published 1900)

Hobson, J. A., & McCarley, R. W. (1977). The brain as a dream state generator: An activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process. American Journal of Psychiatry, 134(12), 1335–1348.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and his symbols. Dell.

Jung, C. G. (1966). Collected works of C.G. Jung: Vol. 11. Psychology and religion: West and East. Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1948)

Jung, C. G. (1968). Collected works of C.G. Jung: Vol. 12. Psychology and alchemy. Princeton University Press.

LaBerge, S. (1985). Lucid dreaming. Ballantine Books.

McAdams, D. P. (1993). The stories we live by: Personal myths and the making of the self. Guilford Press.

Sartre, J.-P. (1992). Being and nothingness (H. E. Barnes, Trans.). Washington Square Press. (Original work published 1943)

Stanner, W. E. H. (1979). White man got no dreaming. Australian National University Press.

Stickgold, R. (2005). Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature, 437(7063), 1272–1278.

Walker, M. P., & van der Helm, E. (2009). Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 731–748.

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. Norton.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,027 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, August 28). Dreams as Personal Myths and 2 Important Theories of It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/dreams-as-personal-myths/