Introduction

We’ve all been there—waiting for exam results, a job interview call, or a medical diagnosis—watching minutes drag by as if the clock were stuck in molasses. The psychological experience of waiting, especially under anxious conditions, can alter our perception of time in strange and distressing ways. But why does waiting feel so torturous when we’re stressed? And how can understanding the science of time perception help us cope better?

Read More- Time Psychology

The Science of Time Perception

The Pacemaker-Accumulator Model

Our understanding of time perception is often explained through the pacemaker-accumulator model (Gibbon, Church, & Meck, 1984). According to this theory, we possess an internal clock that consists of a pacemaker emitting pulses and an accumulator that stores them. The more pulses we register, the longer time feels. Emotional arousal and attention influence this system. When we’re anxious, the pacemaker speeds up, emitting more pulses, which in turn makes time feel longer (Droit-Volet & Meck, 2007; Zakay & Block, 1996).

Attention and Time Distortion

Attention plays a pivotal role in time estimation. When we are focused on time—such as when we’re anxiously waiting for something—we tend to perceive time as moving more slowly (Zakay & Block, 1996). On the other hand, when we are distracted or engaged in an absorbing activity, time flies. Anxiety makes it almost impossible not to attend to the clock, creating a self-perpetuating loop of dread and time distortion.

Anxiety’s Effect on Time

Arousal and Time Overestimation

Anxiety is a state of heightened arousal. Arousal increases the rate at which the pacemaker produces pulses, leading to time overestimation (Droit-Volet & Gil, 2009). This means that when we’re nervous—whether waiting for a doctor’s call or results from a big test—time actually feels longer than it is because our brains are ticking faster.

Research by Yuan, Zhou, and Yang (2020) found that people with high trait anxiety consistently overestimated the duration of negative emotional stimuli. This effect suggests that heightened arousal and negative emotion skew internal timing mechanisms, making distressing experiences feel extended.

Attention Hijacked by Worry

Worry pulls attention away from tasks and toward uncertain outcomes. Grupe and Nitschke (2013) argued that anxious anticipation hijacks cognitive resources, leaving little room for other forms of attention regulation. This mental narrowing not only heightens stress but also prolongs the sensation of waiting.

In one study, participants subjected to uncertainty (like waiting for results) reported that time felt slower and less tolerable than those given clear but negative outcomes (Sweeny & Falkenstein, 2015). The ambiguity itself is more psychologically taxing than bad news—and it distorts our perception of time even further.

The Waiting Spiral

Waiting is rarely neutral. When outcomes are important—health, relationships, career—uncertainty can generate powerful emotions. Rankin, Sweeny, and Xu (2019) found a feedback loop: the more distress people experienced while waiting, the more slowly they felt time passed. This perception of sluggish time increased their anxiety, which in turn made time feel even slower.

Moreover, in their study of law school graduates awaiting bar exam results, those who perceived time as dragging experienced more emotional turmoil, regardless of the final outcome (Rankin et al., 2019). Time perception wasn’t merely a side effect of anxiety—it was an integral part of the waiting experience.

Neurological Mechanisms

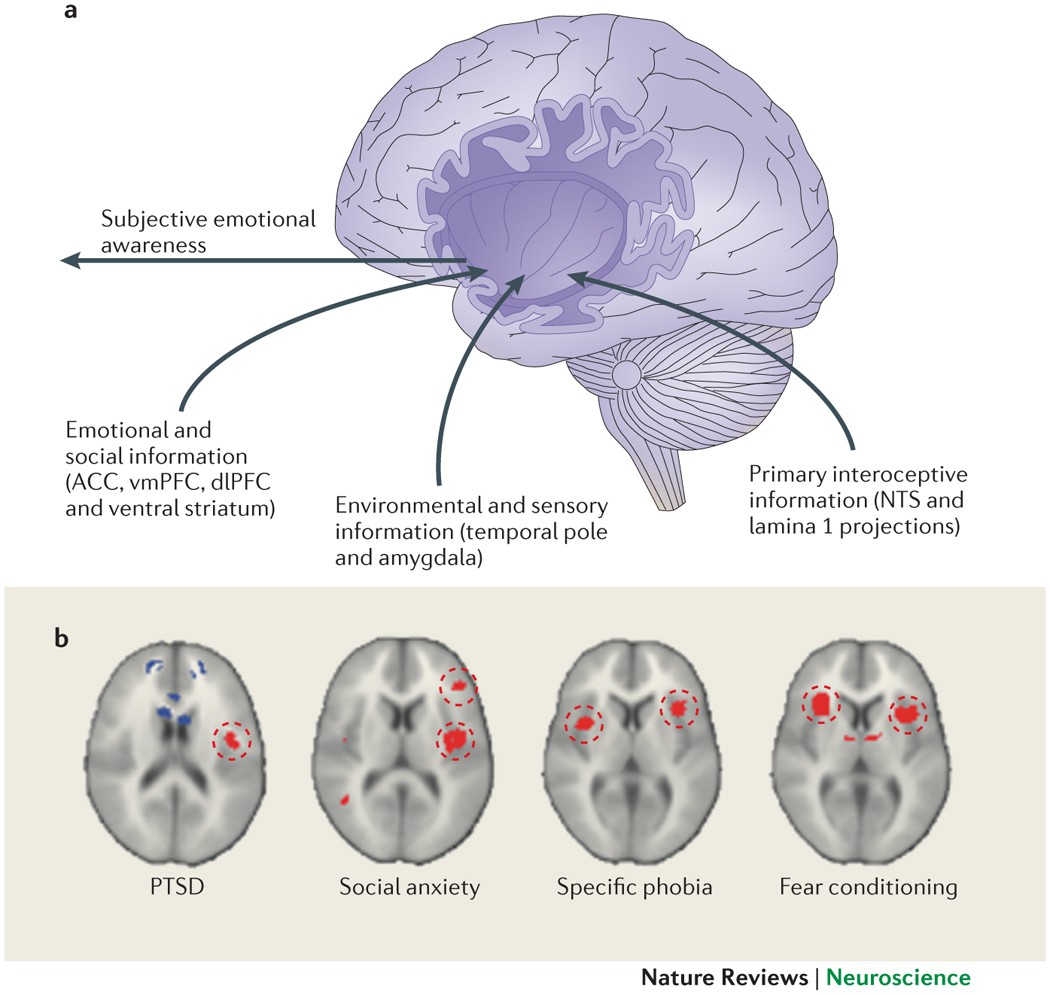

Neuroscientific research provides clues into how the brain processes time under stress. Time perception involves a network of regions, including the insula, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), prefrontal cortex, and basal ganglia (Wittmann, 2013).

Amygdala Activation and Anticipation

The amygdala, our brain’s fear center, is especially active during periods of uncertainty and perceived threat. Grupe and Nitschke (2013) found that anticipatory anxiety engages the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, increasing vigilance and emotional reactivity. This neural engagement alters our perception of time, making moments feel more drawn out.

Additionally, activity in the insular cortex has been linked to interoception—our sense of internal body states—and contributes to subjective time perception, particularly during emotionally charged states (Craig, 2009).

Why Certain Types of Waiting Feel Worse

Not all waiting is created equal. There are several variables that influence how difficult a waiting experience feels.

High Stakes, High Stress

Waiting becomes more agonizing when the outcome feels consequential. Waiting for pizza delivery feels very different than waiting for a cancer diagnosis. When stakes are high, our physiological stress response kicks in, intensifying arousal and altering temporal experience.

Ambiguity and Uncertainty

Uncertainty amplifies distress. Sweeny and Falkenstein (2015) found that people waiting for uncertain outcomes experienced higher levels of anxiety and perceived time as moving more slowly than those who were given definitive, even negative, information. The ambiguity is mentally exhausting.

Lack of Control

Waiting often entails powerlessness, which heightens distress. When we feel like we have no agency over timing or outcome, anxiety increases (Grupe & Nitschke, 2013). This sense of helplessness reinforces the perception that time is dragging.

How to Wait Better

Some ways to make waiting less of a torture are:

1. Label Your Emotions

A basic but powerful strategy from mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is labeling. Simply identifying what you’re feeling—“I’m anxious because I’m waiting for a test result”—helps reduce emotional intensity and creates psychological distance (Lieberman et al., 2007).

2. Schedule Worry Time

Instead of trying to suppress anxious thoughts, allocate a specific time in the day to worry. Galanti (2021) recommends “worry time” as a containment tool. For example, you might set 15 minutes at 6 p.m. each day to write down everything that’s worrying you. This tactic can prevent anxiety from hijacking your entire day.

3. Engage in Flow Activities

The concept of “flow,” coined by Csikszentmihalyi (1990), describes total immersion in an activity. Activities that induce flow—playing music, reading, crafting, or gaming—consume attention and reduce awareness of time. Engaging in flow states during waiting periods helps the hours pass more smoothly.

4. Mental Simulation and Preparation

Imagining both best- and worst-case outcomes reduces the fear of uncertainty. Sweeny and Dooley (2017) argue that “mental rehearsal” for various scenarios can decrease the shock factor of bad news and help you feel more emotionally prepared—regardless of outcome.

5. Use Nature and Environment

Even short interactions with nature reduce stress. A study by Roe et al. (2013) found that time spent in green spaces lowers cortisol levels and improves subjective well-being. Nature also alters time perception, as natural environments are less stimulating in a time-tracking sense, allowing our internal clocks to slow down.

6. Silence and Mindfulness

Intentional silence—even for a few minutes—can reset our sense of time. Pfeifer and Wittmann (2020) discovered that sitting quietly without distraction led participants to feel more grounded and less agitated about passing time. Mindfulness techniques such as deep breathing, body scans, and grounding exercises can reduce arousal and bring attention back to the present moment.

Real-Life Applications

Scenario 1: Waiting in a Hospital

You’re in a hospital waiting room, anticipating test results. Instead of checking your phone every 20 seconds, try a five-minute silent breathing exercise. Focus on the breath, name your emotions, and remind yourself that uncertainty does not equal catastrophe.

Scenario 2: Waiting for a Job Interview Callback

Instead of compulsively refreshing your email inbox, schedule specific times to check messages. Fill the in-between time with engaging tasks: reading, cleaning, or starting a small creative project. Visualize potential outcomes and your reactions to each.

Scenario 3: Waiting for a Response from a Loved One

When emotions are involved, the wait can feel unbearable. Try writing your thoughts in a journal or composing a letter you may never send. Externalizing your thoughts can be therapeutic and regulate emotional intensity.

Conclusion

Waiting is an unavoidable part of life, but understanding how and why anxiety alters our perception of time can help us manage the experience more effectively. Anxiety increases arousal, distorts attention, and accelerates our internal pacemaker—all of which conspire to make time feel longer. But tools like mindfulness, flow, nature exposure, emotional labeling, and scheduled worry can help shrink subjective time and reduce psychological suffering.

Rather than viewing waiting as passive agony, we can treat it as an opportunity: to practice patience, to regulate our emotions, and to grow in resilience. After all, time may not change—but how we experience it certainly can.

References

Craig, A. D. (2009). How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(1), 59–70.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row.

Droit-Volet, S., & Gil, S. (2009). The time–emotion paradox. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1525), 1943–1953.

Droit-Volet, S., & Meck, W. H. (2007). How emotions colour our perception of time. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(12), 504–513.

Galanti, S. (2021). Anxiety relief techniques: How to manage anxious thoughts and emotions. New Harbinger.

Gibbon, J., Church, R. M., & Meck, W. H. (1984). Scalar timing in memory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 423(1), 52–77.

Grupe, D. W., & Nitschke, J. B. (2013). Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(7), 488–501.

Lieberman, M. D., et al. (2007). Putting feelings into words. Psychological Science, 18(5), 421–428.

Pfeifer, E., & Wittmann, M. (2020). Waiting, thinking, and feeling: Variations in the perception of time during silence. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 602.

Rankin, K., Sweeny, K., & Xu, S. (2019). Associations between subjective time perception and well-being during stressful waiting periods. Stress and Health, 35(4), 549–559.

Roe, J., et al. (2013). Green space and stress: Evidence from cortisol measures. Landscape and Urban Planning, 112, 1–9.

Sweeny, K., & Dooley, M. D. (2017). The surprising upsides of worry. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11(4), e12311.

Sweeny, K., & Falkenstein, A. (2015). The psychology of waiting. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(6), 367–372.

Wittmann, M. (2013). The inner experience of time. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1525), 1955–1967.

Yuan, J., Zhou, H., & Yang, J. (2020). Automatic emotion regulation reduces anxiety-related time overestimation. Frontiers in Physiology, 11, 1155.

Zakay, D., & Block, R. A. (1996). The role of attention in time estimation processes. Advances in Psychology, 115, 143–164.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, August 1). The Psychology of Waiting and 6 Mindful Ways to Make It More Bearable. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/psychology-of-waiting/