Introduction

In today’s fast-paced, tech-saturated world, multitasking is often seen as a virtue—an ability prized in the workplace, classrooms, and even our homes. However, the concept of multitasking is riddled with psychological misconceptions. Numerous studies in cognitive science reveal that what we often perceive as multitasking is actually rapid task switching, and this switching carries significant mental costs (Rubenstein, Meyer, & Evans, 2001).

Read More- Decision Fatigue

What Is Multitasking?

In psychology, multitasking refers to the attempt to perform two or more tasks simultaneously. However, most tasks that require conscious attention cannot be genuinely performed in parallel. Instead, people rapidly shift focus from one task to another—a phenomenon known as task switching (Pashler, 1994).

Multitasking can be classified into:

- Concurrent multitasking: Performing two or more activities at the same time (e.g., walking and talking).

- Sequential multitasking: Switching rapidly between tasks that require attention, such as writing an email while attending a virtual meeting.

While some automatic tasks (e.g., breathing or chewing gum) can be combined with attention-heavy ones, the combination of two cognitively demanding tasks almost always results in performance costs (Salvucci & Taatgen, 2008).

The Myth of Efficient Multitasking

One of the most persistent myths is that multitasking increases productivity. In truth, the human brain has a limited cognitive bandwidth and is ill-equipped for managing multiple attention-requiring activities simultaneously.

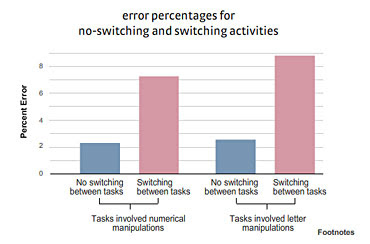

According to research by Rubinstein, Meyer, and Evans (2001), switching between tasks can cause “switch costs,” such as:

- Slower task completion

- Increased error rates

- Higher cognitive load

In one experiment, participants who switched between arithmetic tasks and classification tasks were significantly slower and more error-prone than those who completed each task sequentially (Monsell, 2003).

The Cognitive Cost of Task Switching

When we toggle between tasks, the brain incurs several types of cognitive costs:

1. Time Loss (Switch Costs)

Each time we shift tasks, the brain undergoes a reconfiguration phase—reorienting to new rules, goals, or information (Monsell, 2003). This can take anywhere from a few tenths of a second to several seconds, leading to significant cumulative time loss.

2. Working Memory Depletion

Switching drains working memory, the system responsible for temporarily holding and manipulating information (Baddeley, 2003). This can hinder reasoning, decision-making, and problem-solving.

3. Increased Mental Fatigue

Frequent task switching leads to ego depletion—a concept describing the brain’s diminished capacity for self-control and sustained attention after extensive cognitive exertion (Baumeister et al., 1998).

4. Greater Error Probability

Tasks performed while multitasking tend to have more errors, particularly when they are similar or require overlapping cognitive resources (Logie, Cocchini, Della Sala, & Baddeley, 2004).

Neurological Basis of Multitasking

The prefrontal cortex is central to managing attention and task-switching. Brain imaging studies show that multitasking leads to overactivation in this region, resulting in quicker cognitive fatigue (Just, Keller, & Cynkar, 2008).

In a landmark fMRI study, researchers found that when people tried to perform two tasks at once, their brain split its capacity between the tasks—using one hemisphere per task. However, when a third task was added, performance dropped dramatically, suggesting that the brain can’t handle more than two tasks at once with any degree of efficiency (Dreher & Grafman, 2003).

Individual Differences in Multitasking

Although most people perform poorly when multitasking, individual differences exist. Some people have higher executive functioning, which allows them to switch tasks more efficiently. However, this does not eliminate switch costs; it merely reduces them (Miyake et al., 2000).

Notably, studies have found that those who believe they are good at multitasking often perform worse in lab tests—a phenomenon known as the “multitasking paradox” (Ophir, Nass, & Wagner, 2009).

Multitasking and Technology

Digital devices have amplified multitasking behaviors. Notifications, pop-ups, and simultaneous app use lead to media multitasking—the act of engaging with multiple digital streams simultaneously (e.g., texting while watching TV and browsing online).

This type of multitasking is especially concerning for children and teens. Ophir et al. (2009) found that heavy media multitaskers had poorer attentional control and were more prone to distractions.

Similarly, Sana, Weston, and Cepeda (2013) discovered that even passive exposure to multitasking (e.g., seeing others on laptops during a lecture) impaired learning in college classrooms.

Multitasking in the Workplace

In professional settings, multitasking can appear efficient but often undermines performance. A study by Mark, Gudith, and Klocke (2008) found that office workers took an average of 23 minutes and 15 seconds to return to a task after an interruption, and even longer to regain full concentration.

In high-stakes environments like aviation or surgery, multitasking can have life-threatening consequences. This has led to the design of “task shedding” protocols to prevent cognitive overload (Endsley, 1995).

Gender and Age Differences

Research on gender differences in multitasking is inconclusive. Some studies suggest women are better at certain types of dual-tasking due to differences in brain connectivity (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014), while others find no significant performance differences (Hambrick et al., 2010).

Age, however, shows a clearer pattern. As cognitive flexibility decreases with age, older adults are generally less efficient at task switching (Kray & Lindenberger, 2000).

How to Combat the Multitasking Trap

Some ways to avoid the trap of multitasking include-

1. Monotasking

Train your brain to focus on one task at a time. Use techniques like the Pomodoro Method to structure deep work periods.

2. Digital Hygiene

Silence notifications, close unused tabs, and schedule device-free work sessions to reduce digital distractions.

3. Task Batching

Group similar tasks (e.g., answering emails or making calls) to minimize cognitive switching.

4. Mindfulness Training

Practicing mindfulness enhances attentional control and reduces automatic task switching (Zeidan et al., 2010).

Conclusion

Multitasking, especially involving cognitively demanding tasks, is largely a myth. Rather than boosting efficiency, it compromises attention, increases errors, and saps cognitive energy. Understanding the true costs of task switching can help individuals and organizations design better workflows, educational models, and digital experiences.

To thrive in the attention economy, we must retrain our minds for focus—not fragmentation.

References

Baddeley, A. D. (2003). Working memory and language: An overview. Journal of Communication Disorders, 36(3), 189–208.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252.

Dreher, J. C., & Grafman, J. (2003). Dissociating the roles of the medial and lateral anterior prefrontal cortex in human planning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(5), 2847–2852.

Endsley, M. R. (1995). Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Human Factors, 37(1), 32–64.

Hambrick, D. Z., Oswald, F. L., Darowski, E. S., Rench, T. A., & Brou, R. (2010). Predictors of multitasking performance in a synthetic work paradigm. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24(8), 1149–1167.

Ingalhalikar, M., Smith, A., Parker, D., Satterthwaite, T., Elliott, M., Ruparel, K., … & Verma, R. (2014). Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(2), 823–828.

Junco, R. (2012). The relationship between frequency of Facebook use, participation in Facebook activities, and student engagement. Computers & Education, 58(1), 162–171.

Just, M. A., Keller, T. A., & Cynkar, J. (2008). A decrease in brain activation associated with driving when listening to someone speak. Brain Research, 1205, 70–80.

Kray, J., & Lindenberger, U. (2000). Adult age differences in task switching. Psychology and Aging, 15(1), 126–147.

Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 107–110.

May, K. R., & Elder, A. D. (2018). Efficient, helpful, or distracting? A literature review of media multitasking in relation to academic performance. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15, 13.

Monsell, S. (2003). Task switching. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(3), 134–140.

Ophir, E., Nass, C., & Wagner, A. D. (2009). Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(37), 15583–15587.

Pashler, H. (1994). Dual-task interference in simple tasks: Data and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 116(2), 220–244.

Rubenstein, J. S., Meyer, D. E., & Evans, J. E. (2001). Executive control of cognitive processes in task switching. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27(4), 763–797.

Salvucci, D. D., & Taatgen, N. A. (2008). Threaded cognition: An integrated theory of concurrent multitasking. Psychological Review, 115(1), 101.

Sana, F., Weston, T., & Cepeda, N. J. (2013). Laptop multitasking hinders classroom learning for both users and nearby peers. Computers & Education, 62, 24–31.

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), 597–605.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,040 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, June 22). Myth of Multitasking and 4 Important Cognitive Costs of It. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/myth-of-multitasking/