Introduction

In an era dominated by smartphones, cloud storage, and AI-powered reminders, our ability to remember information has undergone a seismic shift. The phenomenon known as Digital Amnesia, a term popularized by cybersecurity firm Kaspersky Lab, refers to the tendency to forget information that is stored and easily accessible through digital devices. While convenience is undeniable, the growing dependence on external memory aids poses critical questions for psychology and cognitive science. How is this affecting our memory systems? Are we losing cognitive strength, or simply adapting to a new form of information processing?

Read More- Emotional Labour

What Is Digital Amnesia?

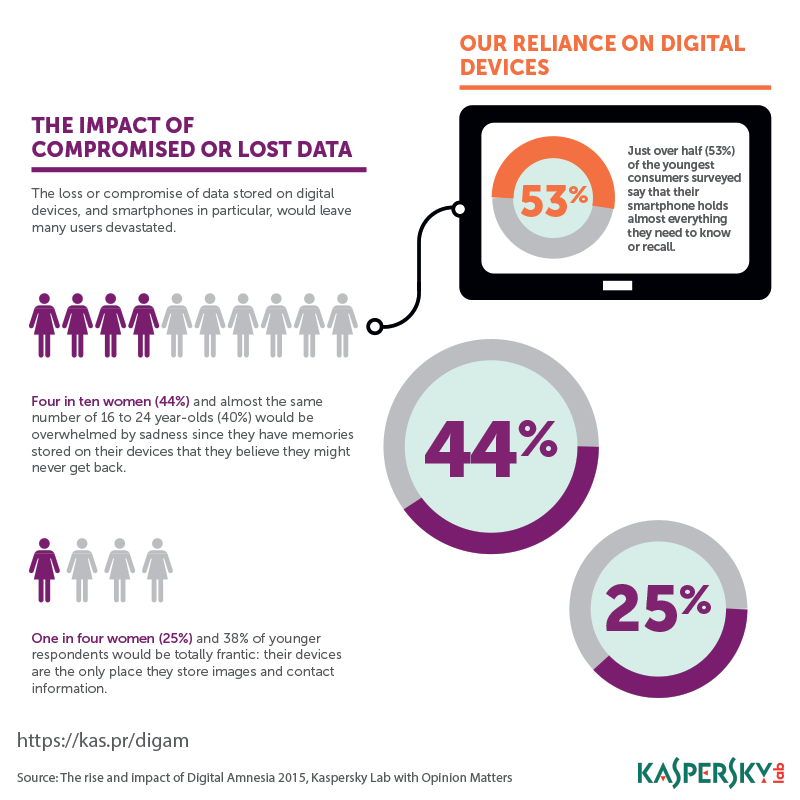

Digital Amnesia is the experience of forgetting information that one expects a digital device to remember for them. This includes phone numbers, passwords, appointments, and even basic facts. According to a 2015 study by Kaspersky Lab, 91% of people in the U.S. and Europe admitted to using the internet as an online extension of their memory, and more than 40% were not able to recall important phone numbers, including their partner’s.

This behavior stems from a psychological phenomenon called the “Google Effect” (Sparrow et al., 2011), where people are less likely to retain information if they believe it is accessible online. In essence, we are outsourcing memory—not unlike writing things down in a notebook, but on a vastly larger and more integrated scale.

Memory Systems in the Brain

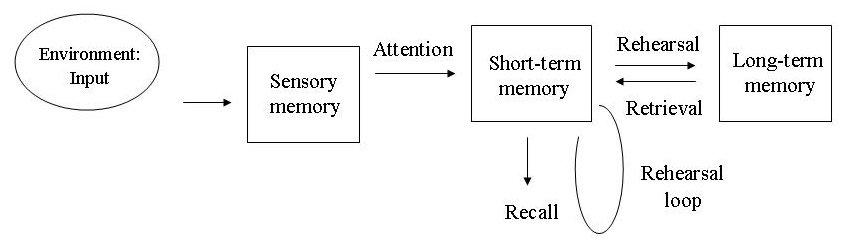

To understand the impact of digital amnesia, we must look at how memory works. Human memory is broadly divided into:

- Sensory Memory

- Short-Term (Working) Memory

- Long-Term Memory

Encoding, storage, and retrieval are the three fundamental processes involved. The act of encoding—the initial learning of information—requires attention and effort. Devices that reduce our need to encode information also reduce the likelihood that it will be stored in long-term memory (Baddeley, 1992).

When we rely on digital devices, we often skip the encoding process. For example, instead of memorizing a grocery list, we save it to our phones. As a result, the brain is never forced to store or retrieve that information from memory, weakening the neural connections that support memory recall.

Transactive Memory

The concept of Transactive Memory (Wegner, 1985) refers to a shared system for encoding, storing, and retrieving information among individuals or systems. In a marriage, for instance, one partner might remember family birthdays while the other recalls financial data.

Digital devices now serve as transactive memory systems—but unlike human partners, they do not require mutual understanding or relationship development. This outsourcing of cognitive responsibility has clear benefits in efficiency, but it may be weakening our epistemic agency—our ability to form and trust our own knowledge.

Cognitive Offloading and Its Consequences

“Cognitive offloading” is the act of relying on external tools to manage cognitive tasks. Smartphones are primary tools for this, handling everything from directions to arithmetic. While offloading reduces mental load and frees cognitive resources for other tasks, it can also:

- Reduce memory retention

- Decrease problem-solving capacity

- Lower learning engagement

A study by Barr et al. (2015) found that people who frequently used smartphones to look up information rather than using memory had lower cognitive reflection scores. In other words, habitual offloaders may struggle to think through complex problems independently.

Neuroplasticity and Adaptation

A counter-argument to digital amnesia is based on the concept of neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize itself. It’s possible that we are not losing capacity, but rather repurposing it. As we offload certain kinds of memory tasks, we may be developing other cognitive skills such as navigation of digital systems, multitasking, and creative problem solving.

However, this reallocation is not without consequences. Studies show that the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center, shrinks in size when underused (Maguire et al., 2000). Long-term reliance on digital memory aids may have a measurable impact on brain structure and function.

Emotional and Social Impacts

Memory is tied not just to information, but also to identity and emotion. Remembering events, names, and stories helps us build and maintain relationships. When we forget these in favor of what our phones can store, we may face:

- Social consequences (e.g., forgetting a friend’s birthday)

- Loss of personal narrative continuity

- Dependence anxiety when devices are unavailable

In clinical psychology, memory impairment is often associated with conditions like dementia and depression. While digital amnesia is not pathological, it mimics some of the disconnections these conditions produce—suggesting a subtle, creeping cost.

Generational Differences and Educational Impact

Digital natives—those born after the mid-1990s—are growing up in a world where offloading memory is normal. A 2019 study by Sparrow and Chatman found that students were less likely to remember facts they believed were available online, even when told they would be tested.

In education, this means we must balance teaching content with teaching information navigation. Memorization is not obsolete, but its role is changing. Some educators advocate for a return to rote learning; others suggest that fostering metacognition—thinking about thinking—is a better path.

Can We Reverse Digital Amnesia?

While digital amnesia is an adaptive response to a changing environment, it’s not irreversible. Strategies to preserve and enhance memory include:

- Active Recall and Spaced Repetition: Re-engaging memory strengthens neural pathways.

- Mindfulness and Attention Training: Being present improves encoding.

- Deliberate Memory Use: Choosing to memorize (e.g., phone numbers, birthdays) builds capacity.

- Digital Hygiene: Limiting overuse of reminders and notes can train internal memory systems.

Apps like Anki, which use spaced repetition, or mindfulness training platforms like Headspace can support better memory function.

Conclusion

Digital Amnesia reflects a broader transformation in how we engage with information and the world. It’s not simply a degradation of memory, but a restructuring of cognitive priorities. As we lean more on technology, we must be intentional about how we preserve our memory capacities, personal agency, and mental autonomy.

Rather than rejecting technology, we can consciously integrate it—balancing offloading with mental exercise, and convenience with cognition. The future of memory may lie not in remembering more, but in remembering what matters most.

References

Baddeley, A. D. (1992). Working memory. Science, 255(5044), 556-559.

Barr, N., Pennycook, G., Stolz, J. A., & Fugelsang, J. A. (2015). The brain in your pocket: Evidence that smartphones are used to supplant thinking. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 473–480.

Kaspersky Lab. (2015). Digital Amnesia Study. https://www.kaspersky.com/blog/digital-amnesia-report/

Maguire, E. A., Gadian, D. G., Johnsrude, I. S., et al. (2000). Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(8), 4398–4403.

Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science, 333(6043), 776–778.

Wegner, D. M. (1985). A computer network model of human transactive memory. Social Cognition, 3(2), 140–160.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,042 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, June 18). What is Digital Amnesia and 4 Important Ways to Reverse Them. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/digital-amnesia/

Pingback: Too Much Screen Time May Train Your Brain to Forget More Easily