Introduction

Why are some people naturally outgoing while others prefer solitude? Why do siblings raised in the same household often develop strikingly different personalities? These questions lie at the heart of one of psychology’s oldest and most debated topics: nature vs. nurture. The debate explores how much of who we are is shaped by our genetic makeup (nature) and how much is influenced by our environment and life experiences (nurture).

For decades, psychologists argued over whether personality is primarily inherited or learned. Today, research suggests the answer is far more nuanced. Personality emerges from a dynamic interaction between biological predispositions and environmental influences, unfolding across the lifespan.

Read More: Sleep and Mental Health

What Is Personality?

Personality refers to consistent patterns of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that distinguish individuals from one another. According to trait theories, personality is relatively stable over time and situations, though not entirely fixed.

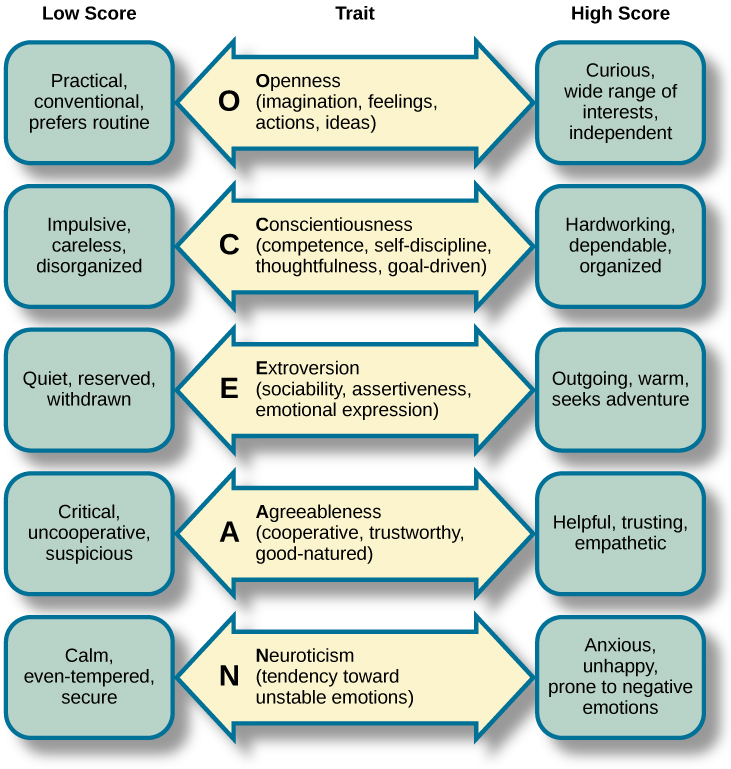

One of the most widely accepted models is the Five-Factor Model (FFM), often called the Big Five, which includes:

- Openness to experience

- Conscientiousness

- Extraversion

- Agreeableness

- Neuroticism

These traits exist on continua rather than as fixed categories, and individuals fall at different points along each dimension (McCrae & Costa, 1997).

Understanding how these traits develop requires examining both biological and environmental factors.

The Case for Nature

The case for nurture can be made on the following parameters:

1. Genetic Influences on Personality

Twin and adoption studies provide some of the strongest evidence for genetic influences on personality. Identical twins share nearly 100% of their genes, while fraternal twins share about 50%. If personality traits are strongly genetic, identical twins should be more similar than fraternal twins — and research consistently supports this.

Large-scale studies suggest that 40–60% of personality variation can be attributed to genetic factors (Bouchard, 2004). Traits such as extraversion, neuroticism, and impulsivity show particularly strong heritability.

Importantly, genes do not determine specific behaviors directly. Instead, they influence temperamental tendencies, such as emotional reactivity, energy levels, and sensitivity to stress, which form the foundation of later personality.

2. Temperament

Temperament refers to early-emerging, biologically based behavioral tendencies, observable even in infancy. Psychologist Jerome Kagan’s research identified temperamental differences such as:

- Inhibited vs. uninhibited temperament

- Emotional reactivity

- Sociability

For example, some infants show heightened physiological responses to unfamiliar stimuli, making them more likely to develop shy or anxious personalities later in life (Kagan, 1994).

These temperamental traits are linked to the nervous system, including differences in brain activity, heart rate, and stress hormone responses. While temperament is not destiny, it strongly shapes how individuals interact with their environment.

3. Brain Structure and Neurochemistry

Personality is also influenced by differences in brain structure and neurotransmitter systems. For instance:

- Extraversion has been linked to dopamine sensitivity, which affects reward-seeking behavior.

- Neuroticism is associated with heightened activity in brain regions involved in threat detection, such as the amygdala.

- Conscientiousness correlates with prefrontal cortex functioning, which supports self-control and planning.

These biological differences help explain why people respond differently to the same situations, even when raised in similar environments (DeYoung, 2010).

The Case for Nurture

The case for nurture can be understood across 3 parameters:

1. Family and Parenting

Early family experiences play a critical role in shaping personality development. Parenting styles — authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and neglectful — influence traits such as emotional regulation, self-esteem, and social competence.

For example:

- Warm, responsive parenting is associated with higher agreeableness and emotional stability.

- Harsh or inconsistent parenting increases the risk of anxiety, aggression, and low self-control.

However, it is important to note that children are not passive recipients of parenting. Their temperaments influence how parents respond to them, creating a bidirectional relationship between child and environment.

2. Culture and Social Context

Culture profoundly shapes personality expression and values. Individualistic cultures (e.g., the United States) tend to emphasize independence, assertiveness, and personal achievement, while collectivistic cultures (e.g., many East Asian societies) prioritize harmony, cooperation, and social responsibility.

Research shows that:

- Extraversion and self-promotion are more socially rewarded in individualistic cultures.

- Traits such as modesty and interdependence are more valued in collectivistic contexts.

These cultural norms influence not only behavior but also how individuals perceive themselves, shaping identity and personality over time (Markus & Kitayama, 1991).

3. Life Experiences and Learning

Significant life events — trauma, education, relationships, career challenges — leave lasting imprints on personality. For example:

- Chronic stress can increase neuroticism.

- Leadership roles may enhance confidence and assertiveness.

- Long-term relationships can foster emotional maturity and empathy.

Learning processes such as reinforcement, modeling, and social feedback gradually shape habitual patterns of behavior, supporting the nurture perspective.

Moving Beyond the Debate

Modern psychology largely rejects the idea that nature and nurture operate independently. Instead, personality is understood through interactionism, which emphasizes continuous interplay between genes and environment.

Gene-Environment Interaction

Genes influence how people respond to environmental experiences, and environments influence how genes are expressed. For instance:

- A child genetically predisposed to impulsivity may thrive in a structured environment but struggle in a chaotic one.

- Individuals with a genetic vulnerability to depression may only develop symptoms under prolonged stress.

This interaction helps explain why people with similar genetic predispositions can develop very different personalities depending on their environments.

Epigenetics

Epigenetics provides a biological mechanism for the nature–nurture interaction. Environmental factors such as stress, nutrition, and caregiving can activate or deactivate genes without changing DNA sequences.

Studies show that early-life adversity can alter stress-response systems, affecting emotional regulation and personality traits well into adulthood (Meaney, 2010). This research highlights how nurture can leave lasting biological marks.

Personality Development Across the Lifespan

Contrary to earlier beliefs, personality continues to change throughout life. Longitudinal studies show that:

- Conscientiousness and emotional stability tend to increase with age.

- Impulsivity and neuroticism often decrease over time.

These changes are influenced by social roles, responsibilities, and accumulated life experiences, demonstrating ongoing interaction between internal dispositions and external demands (Roberts et al., 2006).

Implications for Mental Health and Society

Understanding personality formation has important practical implications:

- Mental health: Recognizing genetic vulnerabilities can improve prevention and treatment strategies.

- Education: Tailoring learning environments to individual temperaments can enhance outcomes.

- Parenting: Appreciating temperament differences encourages more responsive caregiving.

- Social policy: Acknowledging environmental impacts underscores the importance of supportive communities.

Rather than asking whether nature or nurture matters more, a more productive question is how they work together to shape human individuality.

Conclusion

The nature versus nurture debate is no longer about choosing sides. Personality is neither written entirely in our genes nor solely molded by experience. Instead, it emerges from a complex, lifelong dialogue between biology and environment.

Genes provide the blueprint, temperament sets the tone, and life experiences shape expression. Culture, relationships, and personal choices further refine who we become. Understanding this interplay not only deepens our knowledge of human behavior but also fosters empathy — reminding us that personality differences reflect both inherited diversity and lived experience.

References

Bouchard, T. J. (2004). Genetic influence on human psychological traits. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(4), 148–151.

DeYoung, C. G. (2010). Personality neuroscience and the biology of traits. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(12), 1165–1180.

Kagan, J. (1994). Galen’s prophecy: Temperament in human nature. New York: Basic Books.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52(5), 509–516.

Meaney, M. J. (2010). Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene × environment interactions. Child Development, 81(1), 41–79.

Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 1–25.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,044 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2026, January 2). Nature vs. Nurture and 3 Powerful Evidence for Each. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/nature-vs-nurture/

Pingback: Homepage