Introduction

Gender and Happiness is one of the most important interaction of two variables. Happiness, often referred to as subjective well-being (SWB), evolves across the lifespan and is influenced by various genetic, environmental, social, and psychological factors. Positive psychology plays a key role in understanding these changes, with concepts like emotional regulation, gratitude, and social connections being central to sustaining well-being at different life stages.

Subjective Well-Being (SWB) is a concept central to positive psychology, SWB consists of-

- Affective well-being- The balance of positive and negative emotions.

- Cognitive well-being- Life satisfaction, an evaluation of one’s life circumstances (Diener, 1984).

Happiness can also be defined as a positive emotional state that arises when individuals feel satisfied with their life and experience frequent positive emotions, such as joy or contentment, and relatively few negative emotions. It reflects both emotional well-being and a cognitive evaluation of life satisfaction (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005).

Read More- What is Happiness?

Theories of Happiness

1.Hedonic Adaptation Theory or Set-Point Theory-

it suggests that individuals have a relatively stable baseline or “set-point” of happiness, influenced largely by genetics. Life events—both positive (e.g., marriage, promotions) and negative (e.g., loss, illness)—cause temporary fluctuations in happiness, but over time, people tend to return to their baseline level of happiness.

This theory emphasizes the idea that while external circumstances can temporarily change happiness, individuals naturally adapt and return to their set-point over time (Brickman & Campbell, 1971).

2. Authentic Happiness Theory-

It was developed by Seligman and posits that true happiness arises from living a life that fulfills three core components. The first component is Pleasure, which refers to the pursuit of enjoyable experiences and positive emotions, essential for a fulfilling life, even if they are often transient.

The second component is Engagement, achieved through deep involvement in activities that challenge an individual’s skills and abilities, closely related to the concept of “flow,” where one becomes fully immersed in a task, leading to a profound sense of fulfillment and satisfaction.

The third component is Meaning, which involves finding purpose and belonging, connecting to something larger than oneself, such as family, community, or spirituality. According to Seligman, cultivating these elements fosters a more fulfilling and joyful life.

3. Flow Theory-

It was developed by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, suggests that true happiness is attained through a state of “flow,” which occurs when individuals become fully immersed in activities that challenge their skills while providing clear goals and immediate feedback.

This state is characterized by intense concentration, a sense of control, and intrinsic enjoyment, leading to deep satisfaction. Key conditions for achieving flow include a balance between challenge and skill, clear goals, immediate feedback, and high concentration.

Csikszentmihalyi posits that regularly experiencing flow can enhance happiness and life satisfaction by fostering a sense of accomplishment and mastery, emphasizing the importance of engaging in activities that induce this optimal experience.

Read More- Measure My Happiness Levels (Oxford Happiness Questionnaire)

Gender and Happiness

Most research indicates no significant overall difference between men and women in happiness levels. While men and women exhibit different emotional experiences, their overall happiness is largely similar.

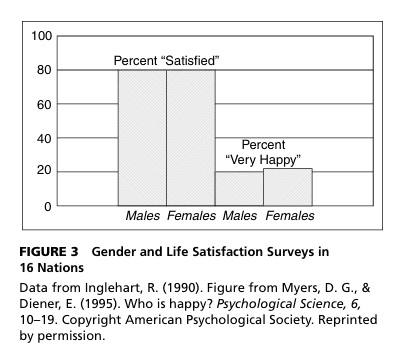

Numerous surveys and studies, including those covering nearly 170,000 people across 16 nations, show that men and women report approximately equal levels of life satisfaction (Inglehart, 1990).

Other studies reinforce this general finding, indicating minimal differences in subjective well-being (SWB) between the sexes (Diener et al., 1999; Manstead, 1992).

Read More- Mental Health

Gender Paradox

- Despite emotional differences, overall happiness remains the same between men and women. This is known as the “gender paradox” of happiness, where emotional disparities coexist with similar happiness levels.

- Studies consistently show that while men and women report different emotional lives, their overall levels of happiness are nearly identical. For example, meta-analyses have shown slight tendencies favoring one gender over the other, but these differences are minor (Haring et al., 1984; Wood, Rhodes, & Whelan, 1989).

- Knowing a person’s gender alone tells very little about their happiness, as gender differences in emotional experiences do not necessarily translate to significant differences in overall well-being.

Why Does the Paradox Occur?

- Emotional Intensity– Some researchers argue that women experience emotions more intensely, both positive and negative. This heightened emotional intensity may result in an averaging out of extremes, balancing their overall happiness to be comparable to men’s (Diener et al., 1999; Fujita et al., 1991).

- Stereotypical Expectations– Gender stereotypes, which depict women as more emotional and men as more stoic, may shape how individuals report their emotions. These stereotypes can lead to biases in self-reported emotional experiences, where women may recall and report emotions in ways that align with societal expectations (Brody & Hall, 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema & Rusting, 1999).

- Methodological Issues– Research shows that when emotions are measured in real-time through methods like experience sampling, gender differences in emotional experience are smaller than those found in retrospective reports, which are more influenced by stereotypes (Robinson & Johnson, 1997).

Dimension 1. Gender Differences in Emotional Expression

Negative Emotions

- Externalization vs Internalization- Women are more likely to suffer from internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety. These conditions typically emerge earlier in life for girls, appearing between the ages of 11 and 15, while no such early onset is found in boys (Kessler et al., 1994; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995). Women tend to experience and express negative emotions such as sadness, fear, anxiety, shame, and guilt more frequently than men (Brody & Hall, 1993; Feingold, 1994). Men have significantly higher rates of externalizing behaviors such as aggression, substance abuse, and antisocial personality disorder (Nolen-Hoeksema & Rusting, 1999).

- Aggression- Physical aggression is more common in men, with studies across 20 countries finding consistent evidence of this trend. However, circumstances, social norms, and context can influence when and how each gender expresses aggression (Archer, 2005; Bettencourt & Miller, 1996). Women are more likely to engage in verbal and relational aggression, such as damaging another person’s social relationships or reputation (Archer & Coyne, 2005).

Positive Emotions

- Mixed Findings- Research on positive emotions like happiness, joy, and love reveals somewhat inconsistent gender patterns. Some studies suggest that women report higher levels of happiness, while others find no significant difference or slightly more happiness among men (Diener et al., 1985; Fujita et al., 1991).

- Emotional Expression- Women are generally found to express positive emotions more openly than men. Studies indicate that women smile more frequently and are more likely to convey feelings of happiness and love (LeFrance, Hecht, & Paluck, 2003; Halberstadt & Saitta, 1987).

Dimension 2. Eudaimonic Well-being and Gender

- Studies show that men and women have similar levels of overall well-being, but women score higher on dimensions such as positive relationships and personal growth (Ryff & Singer, 2002).

- The eudaimonic view suggests that women’s emotional vulnerabilities may coexist with strengths like empathy and relationship-building, which compensate for these weaknesses. This co-existence of strengths and vulnerabilities explains why women can have similar overall well-being despite experiencing more frequent negative emotions (Ryff & Singer, 2002).

Dimension 3. Emotional Stability-Sensitivity and Well-being

- Emotional Stability- Men tend to experience fewer emotional extremes, which may contribute to a more stable emotional life but may also limit their social well-being (Ryff & Singer, 2000).

- Emotional Sensitivity- Women tend to be more empathetic and sensitive to others, which enhances their relationships but may also increase their susceptibility to negative emotions (Nolen-Hoeksema & Rusting, 1999). There may also exists a compensatory effect. Wherein women’s greater emotional vulnerability may be balanced by their strengths in developing positive relationships, while men’s lower social sensitivity may lead to fewer emotional extremes but less richness in social well-being.

Alternative Genders and Happiness

Research on the happiness and well-being of alternative gender individuals (including transgender, non-binary, and gender non-conforming people) is still evolving, but existing studies highlight several important trends. These include-

- Lower Levels of Happiness- Studies consistently show that third-gender individuals report lower levels of happiness and life satisfaction compared to cisgender individuals (those whose gender identity matches their assigned sex at birth). This disparity is largely attributed to the experiences of discrimination, social stigma, and exclusion faced by third-gender people (Riggle et al., 2014).

- Impact of Discrimination- Experiences of transphobia, social rejection, and lack of access to gender-affirming healthcare significantly contribute to negative mental health outcomes in the third-gender community, such as higher rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation (Meyer, 2015). These factors, in turn, lower overall happiness.

- Importance of Gender Affirmation- Research indicates that individuals who are able to express their gender identity and access gender-affirming treatments, such as hormone therapy and surgeries, report higher levels of happiness and life satisfaction. Gender affirmation can reduce distress and improve overall mental health but the evidence still needs to be evaluated against a controlled group (White Hughto & Reisner, 2016).

Despite these challenges, access to supportive social networks, acceptance, and gender-affirming environments can significantly improve the well-being and happiness of third-gender individuals (Budge et al., 2013). Community belonging and identity pride are key protective factors that enhance happiness levels for this group.

Conclusion

Neither men nor women can be said to be definitively happier. Both genders have unique emotional strengths and weaknesses that offset each other, leading to similar overall levels of happiness.

The emotional lives of men and women differ, but these differences do not result in significant disparities in happiness. Instead, gender-specific strengths and vulnerabilities balance out, creating a complex but ultimately similar picture of happiness for both men and women.

Reference

Budge, S. L., Adelson, J. L., & Howard, K. A. (2013). Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping.

Baumgardner, S. R., & Crothers, M. K. (2009). Positive psychology. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Carr, A. (2011). Positive psychology: The science of happiness and human strengths (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Inglehart, R. (1990). Gender and life satisfaction surveys.

Diener, E., Suh, E., Lucas, R., & Smith, H. (1999). Well-being across cultures: Examining the paradox of gender.

Michalos, A. (1991). Happiness among college students across 39 different countries.

Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Rusting, C. (1999). Gender differences in depression and anxiety: Internalizing disorders.

Brody, L., & Hall, J. (1993). Gender differences in emotional expression: Stereotypes and self-report biases.

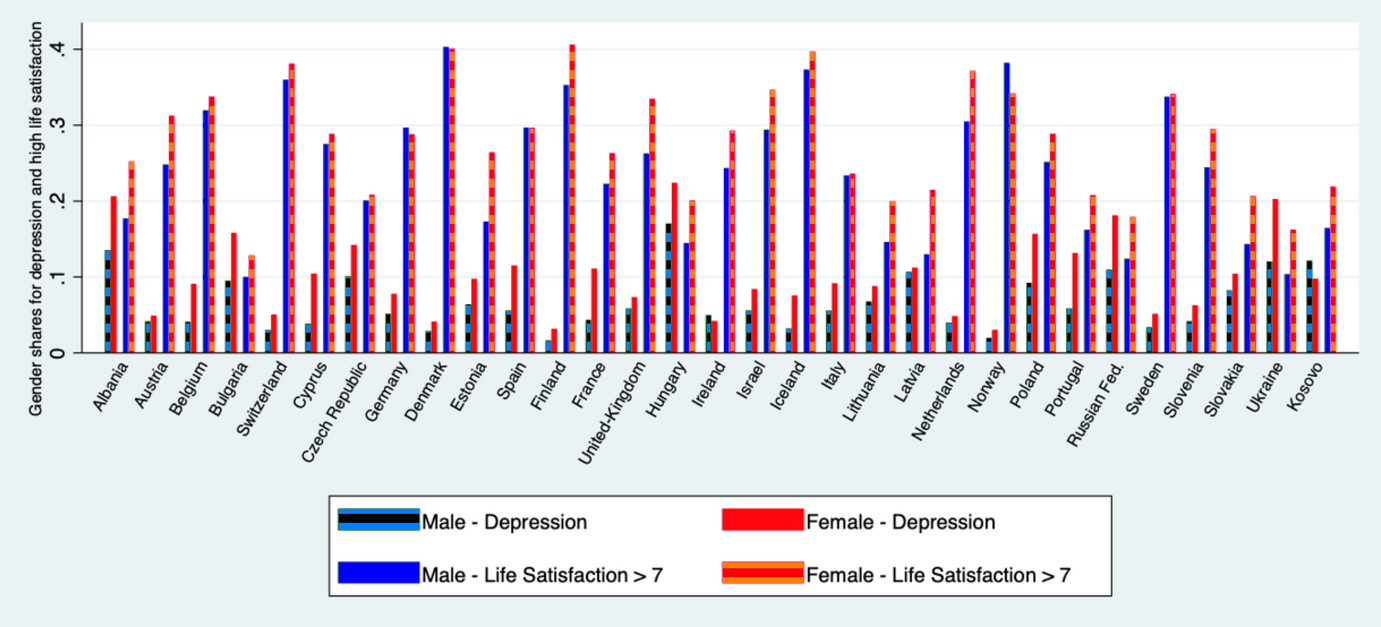

Becchetti, L., & Conzo, G. (2022). The gender life satisfaction/depression paradox. Social indicators research, 160(1), 35-113.

Archer, J. (2005). Gender differences in physical and relational aggression: Meta-analytic findings.

Ryff, C., & Singer, B. (2002). Eudaimonic well-being and psychological health: A new perspective on gender and happiness.

Riggle, E. D. B., Rostosky, S. S., McCants, L. E., & Pascale-Hague, D. (2014). The positive aspects of transgender self-identification: A qualitative study.

LeFrance, M., Hecht, M. A., & Paluck, E. L. (2003). Smiling behavior: Gender differences in positive expressivity.

Robinson, M. D., & Johnson, J. T. (1997). Gender and emotional recall: Stereotype-consistent memory biases.

White Hughto, J. M., & Reisner, S. L. (2016). A systematic review of the effects of hormone therapy on psychological functioning and quality of life in transgender individuals.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,044 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2024, October 29). Understanding Gender and Happiness Across 3 Dimensions. PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/gender-and-happiness/