Introduction

Ever proudly admired a crooked shelf you built yourself—even while silently acknowledging it might collapse under a hardcover book? That’s not just sentimentality. It’s psychology. Specifically, it’s something called the IKEA Effect—a cognitive bias where people place disproportionately high value on products they partially created, regardless of actual quality (Norton, Mochon, & Ariely, 2012).

This article unpacks the psychology behind the IKEA Effect, why we’re emotionally attached to our DIY efforts, and how this principle shapes everything from buying behavior to personal pride.

Read More- Confirmation Bias

What Is the IKEA Effect?

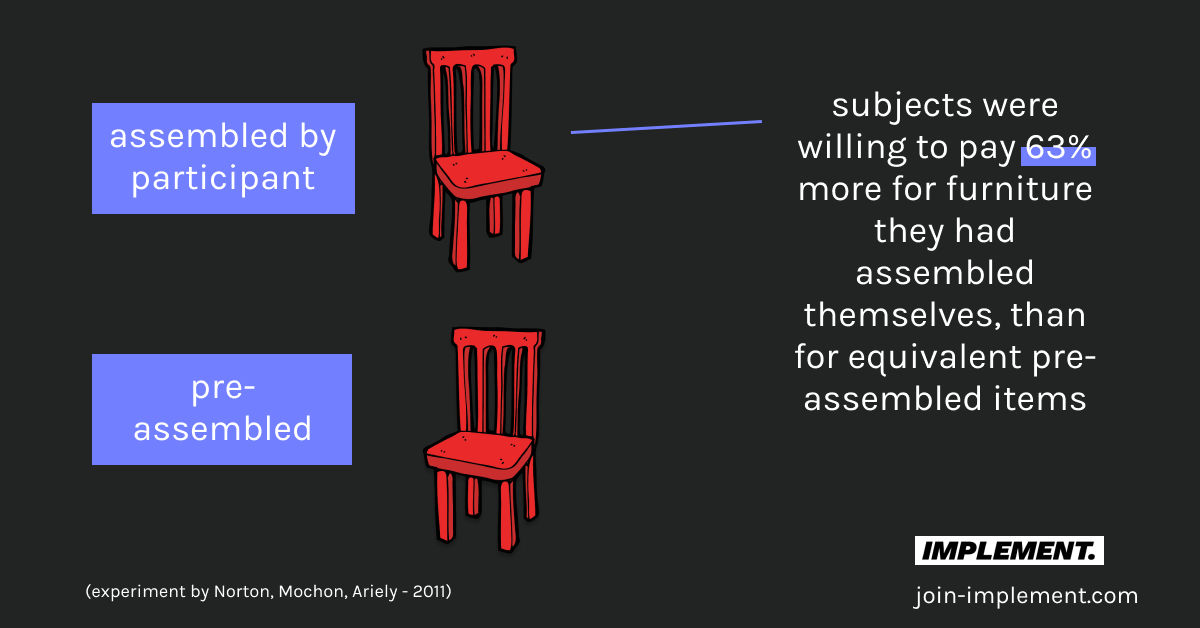

Coined by behavioral economists Michael Norton, Daniel Mochon, and Dan Ariely, the IKEA Effect refers to the tendency to overvalue objects we assemble ourselves—even when those objects are inferior to professionally made alternatives. The term was inspired by IKEA’s flat-pack furniture model, which asks customers to invest labor in the final product.

In one study, participants were asked to build simple origami creations. They were then asked how much they would pay for their own models and others’. Surprisingly, participants valued their own amateurish creations almost as much as professionally made ones—because they made them (Norton et al., 2012).

Why the IKEA Effect Happens

Some reasons why this happens include-

1. Effort Justification

The harder something is, the more we tend to like it. According to the theory of effort justification, when we expend time and energy on a task, we instinctively justify that effort by valuing the outcome more (Aronson & Mills, 1959). That makes your three-hour bookshelf a personal triumph, not a structural hazard.

2. Increased Sense of Ownership

When you build something, you don’t just own it—you created it. This taps into the endowment effect, where people assign greater value to things simply because they belong to them. Add effort to ownership, and the perceived value skyrockets.

3. Emotional Investment

DIY projects require time, focus, and usually some emotional turmoil (and maybe a band-aid). That emotional investment builds a personal narrative around the item—turning an object into a memory.

4. Perceived Competence

Completing a build-your-own task, even a simple one, can boost self-esteem. The IKEA Effect isn’t just about liking the thing—it’s about liking yourself for finishing it. This creates a psychological reward loop that reinforces attachment.

5. Loss Aversion and Sunk Cost Fallacy

Once we’ve put in the work, we don’t want to throw it away—even if it’s flawed. That’s loss aversion and the sunk cost fallacy in action (Arkes & Blumer, 1985). Abandoning a project means admitting the effort was wasted, so we keep it—and value it—even more.

Real-World Implications of the IKEA Effect

Some real-world implications include-

- In Business and Marketing- Brands capitalize on the IKEA Effect by offering customizable or DIY experiences. Think: LEGO, Build-A-Bear, and even meal kits. When customers invest effort, they’re more satisfied—and loyal.

- In Product Design- Designers use the IKEA Effect to boost engagement. Interactive tools, custom dashboards, and user-configured settings all create a sense of “I built this,” increasing user retention and emotional connection.

- In Personal Life- The effect also explains why you might hang on to that amateur painting, or prefer your chaotic homemade birthday cake over a bakery’s version. The imperfections are part of the charm—because you made it.

When the IKEA Effect Can Backfire

While this effect can be empowering, it has downsides. Overvaluing self-made products can lead to bias in judgment, resistance to expert advice, or holding onto bad ideas simply because you built them. In business, this can stifle innovation if teams refuse to abandon flawed internal systems.

Conclusion

The IKEA Effect reminds us that effort is a form of emotional currency. Whether you’re assembling a nightstand, baking bread, or developing an app, the labor you put in increases not just the product’s worth—but your connection to it.

So next time you admire your DIY project (even if it leans slightly left), know this: you’re not being irrational. You’re just human.

References

Norton, M. I., Mochon, D., & Ariely, D. (2012). The IKEA Effect: When Labor Leads to Love. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(3), 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.08.002

Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The Effect of Severity of Initiation on Liking for a Group. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59(2), 177–181.

Arkes, H. R., & Blumer, C. (1985). The Psychology of Sunk Cost. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 35(1), 124–140.

Subscribe to PsychUniverse

Get the latest updates and insights.

Join 3,036 other subscribers!

Niwlikar, B. A. (2025, April 27). The IKEA Effect: 5 Reasons Why We Love the Things We Build (Even When They’re Flawed). PsychUniverse. https://psychuniverse.com/the-ikea-effect/

Pingback: URL

Pingback: Giải pháp hỠtrợ thoải mái